Of all the documents that companies produce, proxy statements are among the most useful for reporters.

It’s all in there, and more. But it isn’t always easy to piece together. These posts serve as an introductory field guide to the document. Along the way, we’ll see how proxies can help you break news, add context to articles and even develop story ideas.They tell you what the top bosses are paid, from cash and stock to free jet rides. They lay bare conflicts of interest that entangle executives and board members. They let shareholders vote on everything from mergers to hot political issues. They can even provide a front-row seat to brawls between a company and powerful shareholders.

Proxies are too varied for any guide to be comprehensive.

I’ll focus on the kind you’re most likely to run into: annual proxy statements issued by U.S. companies that are publicly traded (i.e., have shares traded on exchanges or markets such as the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq). Very small public companies, closely held companies, and firms based outside the U.S. generally follow different rules.

Also, remember disclosure rules change, new issues emerge and specific industries and companies often present distinct challenges. Luckily, clarity is usually only a few mouse clicks or phone calls away.

What a proxy is — and isn’t

As useful as they are, proxies aren’t written for reporters. They amount to an open letter to a company’s shareholders, and federal securities rules require much of the information to be presented in consistent, systematic ways. As a result, it’s more accessible than many corporate filings.

Most fundamentally, annual proxy statements tell shareholders what they can vote on at the company’s annual meeting. Typically, that’s electing or re-electing company directors (board members), approving the company’s auditor, and voting on any proposals made by management or shareholders.

But companies are supposed to include context and background to give investors an informed choice. That makes it a wellspring of data and insight for reporters writing about the same topics, and many others. Most of the information covers the prior fiscal year, but some looks back further than that.

Keep reading or take an 8-minute tour through Proxy Statements with Theo Francis.

Walking through Apple’s Proxy Statement with Theo Francis from Reynolds Center on Vimeo.

Who files proxy statements

Most proxies are filed by the company itself: written by the company, from the company’s perspective. As a result, the formal conclusions and recommendations tend to be predictable. The data, explanations and context are usually more useful for reporters.

Some proxies are filed by other parties. The most common alternative: Investors seeking to oust some or all of a company’s board. That’s called a proxy battle, and almost always means news.

When proxy statements are filed

As a practical matter, look at when a company filed its last annual proxy statement — the next one will probably appear about a year later. If the company won’t say when it plans to file, keep checking around that date.

The precise timing is governed by a mesh of state and federal rules, but annual proxy statements typically come out 30 to 60 days before the annual meeting, and usually after the company has filed its Form 10-K.

For many companies — especially “calendar year” companies ending their fiscal years on Dec. 31 — that means the proxy comes out in April or early May. There are plenty of exceptions, though. Apple Inc. ends its year in late September and files its proxy in early January. Poultry giant Tyson Foods Inc. files its proxy in late December.

Companies also file proxy statements ahead of special shareholder meetings, notably those convened to consider a merger or acquisition. These “merger proxies” will be covered in a future guide.

Where to find proxy statements

Companies nearly always post proxy statements (and other key filings) on corporate websites or investor-relations pages. They can also be found through the SEC’s Edgar database; the Resources section also lists links to special search pages. Some companies offer services to make it easier to search and analyze filings, generally for fee; a few are listed under Resources.

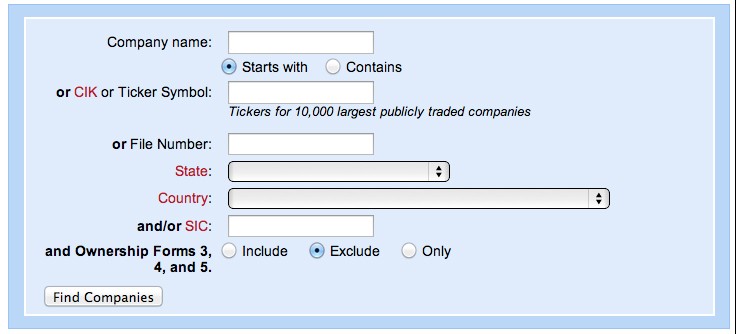

Meet Edgar: A key search form for the SEC’s Edgar database of company filings.

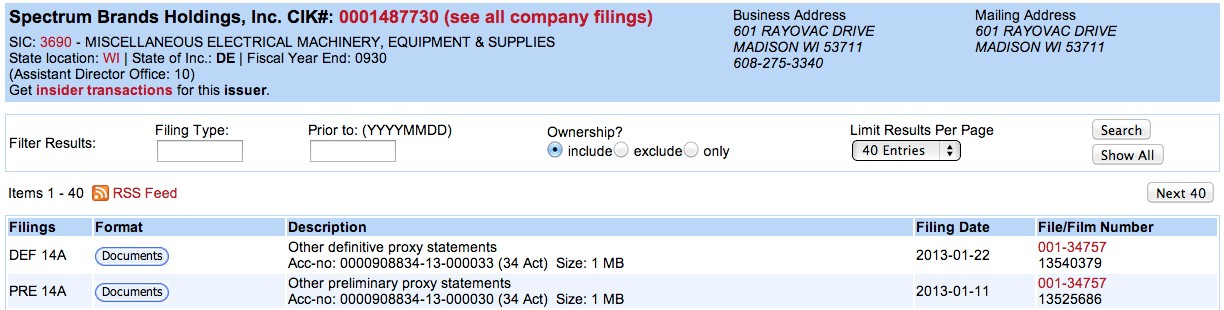

Every kind of filing has a code in Edgar, and a company’s final, “definitive” proxy — the one you’ll use for most stories — is coded as a DEF 14A (after Section 14A of a 1934 securities law that governs the documents). Preliminary proxies, coded as PRE 14A filings, are essentially rough drafts; they can help you get a jump on the competition and are usually filed 10 days or more before the definitive version. Amendments and supplementary documents show up as DEFA14A or PREA14A filings, and there can be several in sequence. Revisions, coded DEFR14A, are rarer.

Search results: Recent definitive and preliminary proxy filings in Edgar from Spectrum Brands Holdings Inc., maker of Black & Decker tools and Cutter insect repellant.

Watch for DEFC14A filings. They’re contested proxy solicitations, a volley in a proxy battle, typically waged by activist investors against a company’s existing management and board. Proxy battles are always newsy. The activist investors lay out their beefs, often in strong terms, in a bid to get shareholders to vote for dissident board candidates. You won’t find these on the company’s website, which is a good reason to get used to using Edgar or a third-party service to do your research. Companies do typically file responses, also coded as DEFC14As, so you may have to wade through multiple rounds of back-and-forth to get the full picture (or a series of follow-ups).