There is a little landmine hidden in the law just waiting to trap the unsuspecting business journalist. Jail could be the result.

The law and journalism are so closely connected that students pursing a journalism degree are almost always exposed to take at least one course on the law. Topics often include covering government and the courts, avoiding obstacles like subpoenas and defamation claims, and the basics of intellectual property, both the use of others’ and the protection of your own.

Insider trading 101

But for the business reporter, a not-so-well-known aspect of securities law poses a very real risk. This is the insider trading rule (§ 240.10b5-1), which bans the trading of securities “on the basis of” material, non-public information. The rule can be traced back to the common law on contracts, which says parties to a contract must put all their cards on the table. Let’s say you are selling you car. A potential buyer asks about the car’s condition and you reply that you haven’t had any trouble with it. So far so good. But what if you didn’t add that when you took the car into the shop the previous week, the mechanic said the transmission was failing and could fall out of the bottom of the car at any time. You tied it up with duct tape and immediately put the car for sale on eBay.

You have withheld material, non-public information. If the unsuspecting buyer completes the transaction and then, discovering the truth, takes you to court, you are likely to find the contact canceled, restitution ordered along with costs and legal fees. A criminal case for fraud could also be in your future.

So, if you work for a company and you see that profits are way up for the current quarter and you know when earnings are reported next week they will greatly exceed expectation, you can’t run out and buy company stock before the announcement. And if you notice that a frighteningly large number of customers are reporting that the batteries in your latest product are exploding and starting fires, and learn that the government is about to order you to recall them, you cannot go out and sell shares. You are going to have to suffer along with every other shareholder.

The stock markets and the Securities and Exchange Commission monitor trading with sophisticated computer systems, looking for trades by corporate insiders and well as usual trading patterns in any stock. They are very good at flagging and then investigating these trades.

The “Heard on the Street” case

Those examples are straightforward and obvious. As a business reporter you’ll finding yourself writing about cases like this. But how does it apply to you personally? Consider the case of R. Foster Winans. Winans was a columnist for The Wall Street Journal who co-wrote the “Heard on the Street Column” from 1982 to 1984. This column, one of the paper’s most popular, offered insights into corporate affairs. It was generally believed to be able to “move” a stock price somewhat depending on its content.

In 1985 Winans was convicted of insider trading. Not for trading on information he gathered from his sources at the companies, but for trading on his knowledge of the columns he had written about the companies but which had not yet been published. Winans didn’t do the trades himself. He passed the information along to a broker, Peter N. Brant, at Kidder, Peabody & Co. Winans admitted to earning money from the scheme, but argued his behavior was unethical but not criminal. Many Wall Street companies argued on Winan’s behalf, claiming the government was overstepping the purpose of the insider trading regulations. Winans lost, the lower courts finding that Winans had, in violation of the rule, “misappropriated” the information, even if the information was the property of his employers, The Wall Street Journal, and not of the companies involved.

The Supreme Court in Carpenter v. United States, deadlocked on this issue, which left the lower court decision in place. In 1987 the Court revisited the case in United States v. James Herman O’Hagan, affirming the misappropriation rule by a vote of 6-3.

In a 2006 speech to business journalists, Christopher Cox, then SEC Chairman, said “Foster Winans, who was found guilty of 59 separate counts of securities fraud, is by no means the only journalist who has stood accused of law breaking, and who brought disgrace to your profession.”

A reporter’s golden rule

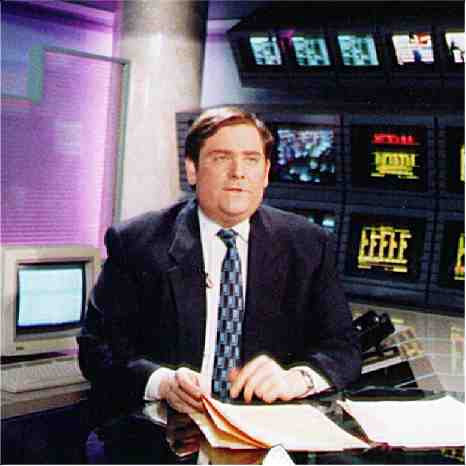

The guideline here is clear: You must treat your unpublished works in progress with care. Their content cannot be used to your financial advantage in stock trading or, for that matter, in any other contractual transaction. At Nightly Business Report, we frequently interviewed the CEOs of major corporations and produced profiles of them and their firms. Our ethical standards made it clear that the very existence of these works-in-progress was to be treated as confidential. Over the years our own rules on stock trading evolved to a point where we were allowed to invest only in large mutual funds and government bonds, not in the stocks or bonds of individual companies.

Reporter’s Takeaway

• Insider trading rules apply to journalists as well as corporate insiders. The repercussions of disregarding them can be serious—including time behind bars.

• Treat your unpublished work-in-progress as confidential. Even a profile of a major corporation’s CEO should be guarded with care.