Prior to an IPO, a company can offer its shares only to investors deemed to be “sophisticated” under the law and therefore able to handle their own due diligence. These are known as private placements. By process of elimination it is apparent that public stock exchanges serve “unsophisticated investors.” That means most of us. The law imposes fairly stringent reporting requirements on companies which list their shares on public exchanges. And the exchanges themselves, which are considered “self-regulating,” impose their own listing requirements on the firms.

NYSE, Amex and NASDAQ

A company’s choice of a primary listing market was once fairly simple. The New York Stock Exchange, the “Big Board,” was for the biggest companies. It required a high market capitalization as a prerequisite for listing. A company’s market cap, one measure of its size and worth, is calculated by multiplying the number of common stock shares outstanding by the current trading price of a share. The NYSE also had the strictness requirements on corporate government and reporting standards. Companies that fell short of the NYSE’s minimum market cap requirements are often listed on the American Stock Exchange (Amex) and still smaller firms listed on the NASDAQ.

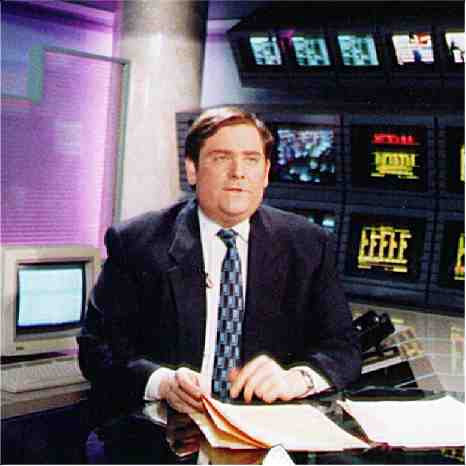

As recently as 1989, when I arrived in New York to cover the stock markets, this described the trading mechanism in the United States. The NYSE, which was born in 1792 as a result of an agreement signed by 24 brokers under a buttonwood tree outside 68 Wall Street (“The Buttonwood Agreement”), and Amex had physical trading floors and used the specialist system. Each listed stock was assigned to a specialist member who acted as an auctioneer and managed all trading in that stock. It was a business that produced a good living for exchange members, both the specialists and those representing public and institutional clients and still allowed time for a nice lunch break, when trading slowed to a crawl, in the members dining room.

The NASDAQ was created as a computerized market without a trading floor. It did not use specialist dealers, but allowed members to “make a market” on shares by posting offers to buy and sell. There were usually many “market makers” for NASDAQ stocks. This low-cost trading option was designed for small, new companies. It was common for companies first listed on the NASDAQ to move to one of the larger exchanges as the company grew. Not any more. Many of the biggest names in the electronic age, including Intel, Microsoft, Apple and Google, elected to stay with the computerized NASDAQ even as they expanded.

Changes on the exchanges

In addition, mergers and acquisitions within the financial services sector, relaxation of regulations to permit a wide range of “specialized” exchanges (including some which are set up to allow computers to trade with each other), and systems allowing big institutional investors like banks, mutual funds, pension funds and money managers to exchange shares directly have pretty much eliminated the differences between the exchanges.

After resisting at first, the NYSE moved into off-floor electronic trading with the purchase of Archipelago, one of the first electronic exchanges. Once planning to buy another building to expand its trading floor, the NYSE is much quieter now. The luncheon club is closed.

There is still heated competition for listings, now on a world-wide scale, even with all the mergers and consolidations. There are two giant surviving public markets, NYSE Euronext and Nasdaq OMX Group. A new company IPO will undoubtedly be listed on one of these.

Reporting trades to the public

With so many exchanges available, most traders don’t know or care where their trade is actually executed. The overriding thrust of current regulations, based in the several hundred page long Securities Exchange Act (available online if you want a little light reading), is that trades on the National Market Systems or what are called Alternative Market Systems must all be reported to the public as quickly as possible (Section 11A). This is generally done through the consolidate tape system, the modern computerized replacement for the original ticker tape invented in the 19th century, which provides the data you see streaming across the screen when you watch the financial news networks or the quotes you get when you go online to make your own trades through your retail brokerage account.

Reporter’s Takeaway

• Traditionally the largest public companies were listed on the NYSE; those with a smaller market cap on the Amex; and new companies on the NASDAQ.

• The last 25 years has seen a dramatic increase in the number of stock exchanges, and the difference between the exchanges has all but been eliminated.

• No matter where a listed stock is traded, the details of the trade, including number of shares and price, must be reported as quickly as possible on the public consolidated quotation system