It is a 10-hour drive or a two-hour flight from Phoenix to San Jose, California, the epicenter of Silicon Valley. The cities’ proximity makes the Phoenix area an increasingly attractive place for semiconductor companies to build the foundries – or fabs, as they are more commonly known – that produce the chips that power Silicon Valley.

Arizona’s Valley of the Sun is ideal for chipmaking. There are no earthquakes and no hurricanes, and – for the time being at least – there is plenty of water for manufacturers’ thirsty fabs, which require tens of thousands of acre-feet of water a year, to use and reuse. An acre-foot – the amount of water it takes to cover an acre of land to a depth of one foot – is equivalent to 325,851 gallons of water or about 30 average swimming pools.

CHIPS for America Act

Another reason chip manufacturers are gobbling up thousands of acres of Valley real estate to build high-tech fabs also has to do with geography: The Valley of the Sun is over 7,000 miles from Taiwan, where over 90% of the most advanced chips are made.

But just 12% of the chips used in the U.S. were manufactured domestically last year, down from 37% as recently as 1990. The disparity illustrates American dependence on Taiwanese product.

That’s why policymakers in Washington are worried that China, which claims Taiwan as a breakaway province, could disrupt that production, either through increasing threats or an outright invasion of the self-governed island, which is 100 miles off the coast of mainland China.

To address those fears, the U.S. House and U.S. Senate introduced in 2020 the CHIPS for America Act, legislation designed to boost domestic chip manufacturing with the help of $52 billion in subsidies. The act’s 30% subsidy to U.S. manufacturers would “level the playing field,” said Michael Fritze, a senior fellow at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, in Arlington, Virginia.

“Initially, it will level the playing field because that 30% is kind of what other countries do to stimulate their own micro-electronics business,” said Fritze, adding that the legislation would also spur semiconductor companies to invest for the future. “Basically, if you put this $52 billion in, and it is, like, over four or five years… it has to be attractive enough so the industry will co-invest to the tune of maybe $150 billion to $200 billion in order to make substantive long-term capability changes for the U.S. The $52 billion by itself is not going to do it, although it will level the playing field.”

President Biden and others have called on Congress to reconcile the two bills that make up the act. However, some companies, including Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), are not waiting on Congress.

With a market capitalization of more than $550 billion, TSMC has purchased 12,000 acres in Biscuit Flats in North Phoenix, near the intersection of State Route 303 and Interstate 17, to build a $12 billion fab scheduled to begin manufacturing chips in 2024. Each month, TSMC will manufacture 20,000 five-nanometer chips, which power iPhones and other high-tech tech products. The company produces 24% of the global supply of semiconductor chips and over 90% of the most powerful chips, including five-nanometer chips.

Chris Camacho, director of the private-public sector partnership Phoenix Economic Council, said the cutting-edge TSMC facility will act as a massive business incubator for the region. Located in what Camacho described as “the new frontier of land in North Phoenix,” the fab’s supporting infrastructure will enable other companies to set up shop nearby.

“That’s going to open up a tremendous amount of technology capability because of the power infrastructure up in that corridor coupled with the City of Phoenix putting in a $200 million-plus water plant to serve this technology corridor… so the next generation of companies that want to come in are going to have infrastructure in place,” he said.

Camacho credited Arizona’s U.S. senators, Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly, with playing vital roles in pushing the CHIPS for America Act forward through the Senate. He said he was hopeful the measure gets approved in the next few months so that companies can move forward with “major billion-dollar investments.”

“It’s going to be pivotal for these companies to operate cost-competitively in the United States, and if somehow [the bill] falls apart and it doesn’t get passed, that will be a core strategic fail of our ability to advance semiconductor production in the United States,” he said.

City of Phoenix Community and Economic Development Director Christine Mackay said she agreed that passage of the CHIPS for America Act would be vital for chip expansion in the Valley, noting that six other semiconductor companies are assessing whether to locate in the Valley but have been unable to do so without the act’s subsidies to offset the labor and material cost advantage enjoyed by Asian manufacturers. Mackay began courting TSMC in 2016, but it wasn’t until the company zeroed in on Biscuit Flats that TSMC settled on Phoenix as the site for what could be four massive fabs.

Mackay said TSMC was looking for a site that it could expand upon, just as it did in Taiwain’s Hsinchu Science and Technology Park: “They wanted a campus with all the support services, with all of their suppliers and training facilities, having business community convening places. They wanted an entire ecosystem.”

Mackay said that is something new for semiconductor manufacturers in the Valley.

“We have a lot of semiconductor companies here today,…[but] they all really work in an isolated environment,” she said, noting that local business Linde Gas and Equipment Inc. is building a $600 million gas-supply plant across from the TSMC facility. And Taiwan-based Sunlit Chemical is building a $100 million, 900,000-square-foot factory east of Biscuit Flats that will produce hydrofluoric acid used in semiconductor manufacturing.

Mackay said the TSMC facility and Intel’s planned $20 billion expansion of its campus in Chandler would generate thousands of well-paying jobs.

“There is no economic multiplier above semiconductors. As they create each job, they are really creating four to six total jobs: the jobs that come into supply them, the jobs that support them,” she said.

And though fabs use enormous amounts of water, she said, the economic value from a gallon of water used in a fab is far greater than that same gallon used on a golf course or in another industry, especially because much of the water used by fabs is recycled. A fab also will create far more high-paying jobs than a golf course or construction firm will.

The Central Arizona Project and drought

With the opportunity for expansion at Biscuit Flats, TSMC could face the challenge of securing a long-term reliable supply of water to meet the projected demand of 35,000 to 40,000 acre-feet of water a year once its fully built out.

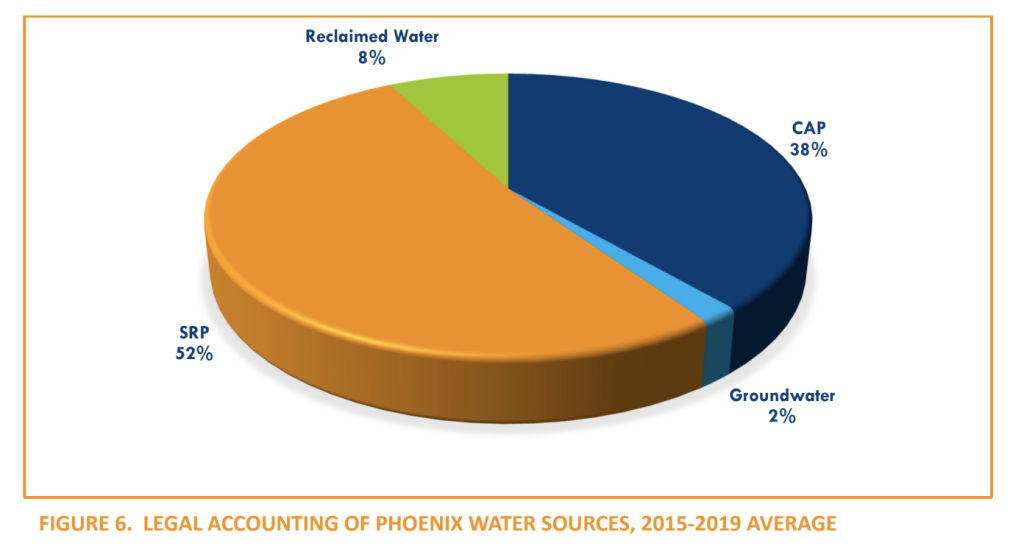

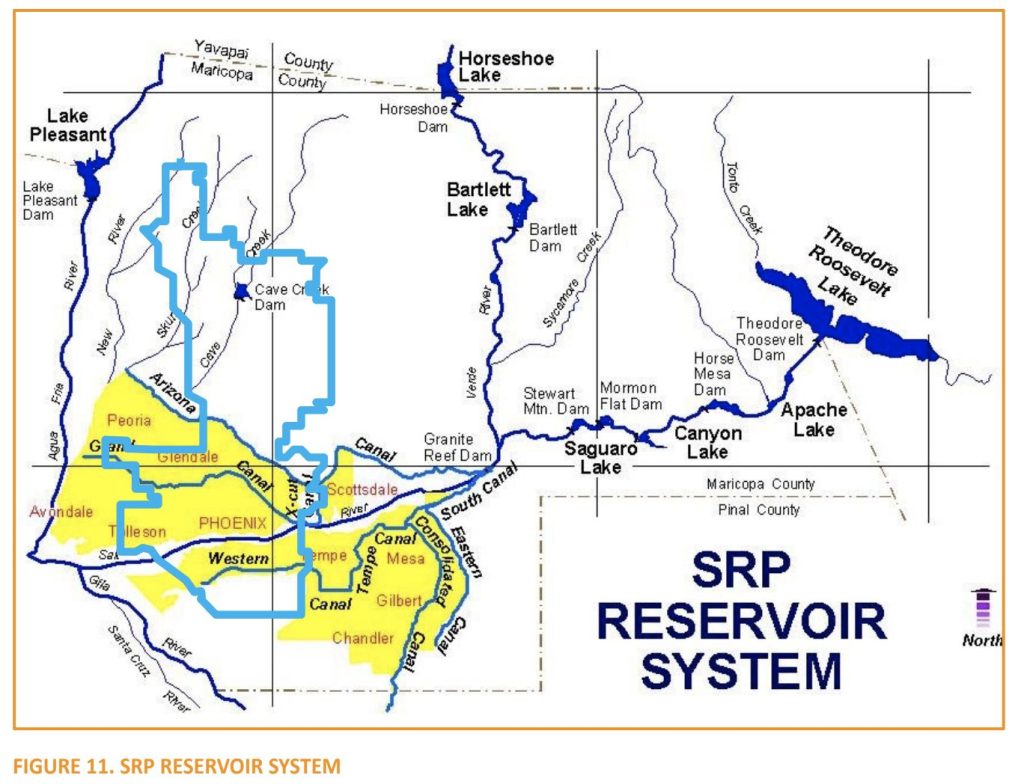

TSMC and nearby facilities will rely almost entirely on water from Central Arizona Project (CAP) – a massive 340-mile system of canals, tunnels and pumping stations that transports Colorado River water from Lake Havasu to Tucson.

CAP, which is administered as a water district by Maricopa, Pinal and Pima counties was finished at a cost of $4 billion in 1993, just a few years before the Southwest entered historic drought conditions. According to the Kyl Center for Water Policy at ASU’s Morrison Institute, there was 18% less water flowing in the Colorado river between 2000 and 2018 than the 20th-century average. The same statistics show that Lake Mead, a holding reservoir, is now at 39% of capacity and water levels dropped below 1,075 feet last year, triggering what is known as a Tier 1 shortage that will result in a cut of 512,000 acre-feet of water this year to CAP water customers. Those cuts, which will amount to 18% of Arizona’s allocation of Colorado River water, will mostly affect agricultural users, Kyl Center Director Kathryn Sorenson said.

“The Colorado River is over allocated. That is the fundamental problem,” Sorenson said. “We pull more from it than it can reliably provide, and that is why the reservoir levels are dropping.”

However, she said, central Arizona can take advantage of multiple sources when it comes to water supply.

“One of the things that a lot of people don’t understand about central Arizona is that we are blessed to have very large and productive groundwater aquifers. In addition to that, we have the flows of the Salt and Verde rivers, and we’ve of course constructed the Central Arizona Project canal to import Colorado River water into our area.”

Arizona is also a leader in reclaiming wastewater and therefore has “built a very robust and diverse water portfolio” that can be used for multiple purposes, she said.

Intel and the city of Chandler

About 40 miles to the southeast of where TSMC is building its massive facility sits Intel’s Ocotillo campus in Chandler, where the company has been manufacturing chips for more than 50 years. Intel recently announced plans to spend $20 billion to build two more fabs on its sprawling 700-acre facility, where close to 12,000 employees work.

Linda Qian, the communications and media relations director for Intel Arizona, said the company produces a “significant amount” of its most advanced products in Arizona and the Chandler site has built-in advantages that will allow Intel to build two facilities with relative ease. “All of our factories on our Ocotillo site are actually connected, so that’s a big advantage so you can run the wafers, the manufacturing process, through those factories. So, the two new factories will be connected to the existing four factories, which does give us advantages over starting a completely new site somewhere else in the Valley.”

Intel has a relatively new 12-acre water treatment plant and reclamation plant on its Ocotillo campus, allowing the company to conserve, treat and reuse a great deal of the water that its factories depend on.

Like TSMC, Intel gets its water from a municipal source, in this case the city of Chandler. The city and Intel have worked closely over nearly a half-century to develop a water-management plant that allows both municipal authorities and Intel to take advantage of water supplies the city gets from both Central Arizona Project and Salt River Project (SRP).

Gregg Capps, Chandler’s utilities resources manager, said all of the water Chandler gets from Intel’s water-reclamation facility – is re-used. The site is large enough to allow Intel to build out its two new fabs without causing the city to adjust its water requirements because the company has essentially developed a closed system in which the only water lost is that which has evaporated in its cooling towers.

“So, by building this onsite facility, that has really helped them with their expansion because now they are recirculating their water in their site,” said Capps, who has been involved in water-management issues in Chandler for more than two decades. One of the keys to successful water management in the Valley, he said, is to recycle large amounts of water and then recharge or inject it back into the aquifer so that in times of drought or long-term aridification, municipalities can use more groundwater to deal with potential shortages.

Qian, of Intel, said the company uses a lot of water but also conserves a lot, pumping it to restoration projects. Of the 12,566 acre-feet of freshwater and 3,242 acre-feet of reclaimed water that Intel received from Chandler in 2020, the company discharged about 12,971 acre-feet and conserved more than 5,674 acre-feet, she said.

“So between what we took out and what we discharged, there was a difference of about two-thousand megaliters (1,621 acre feet), which was lost to evaporation and irrigation, and that’s where those restoration projects in the community come into play.” Qian said Intel currently returns and restores about 95% of its freshwater withdrawals and is aiming to achieve net positive water use by 2030.

Chandler gets about 60% of its water from Salt River Project lands and about 40% from CAP, which gives it a diversified water supply. In a severe drought, that diversity could provide an advantage over companies such as TSMC, which will rely on CAP for nearly 100% of its water supply.

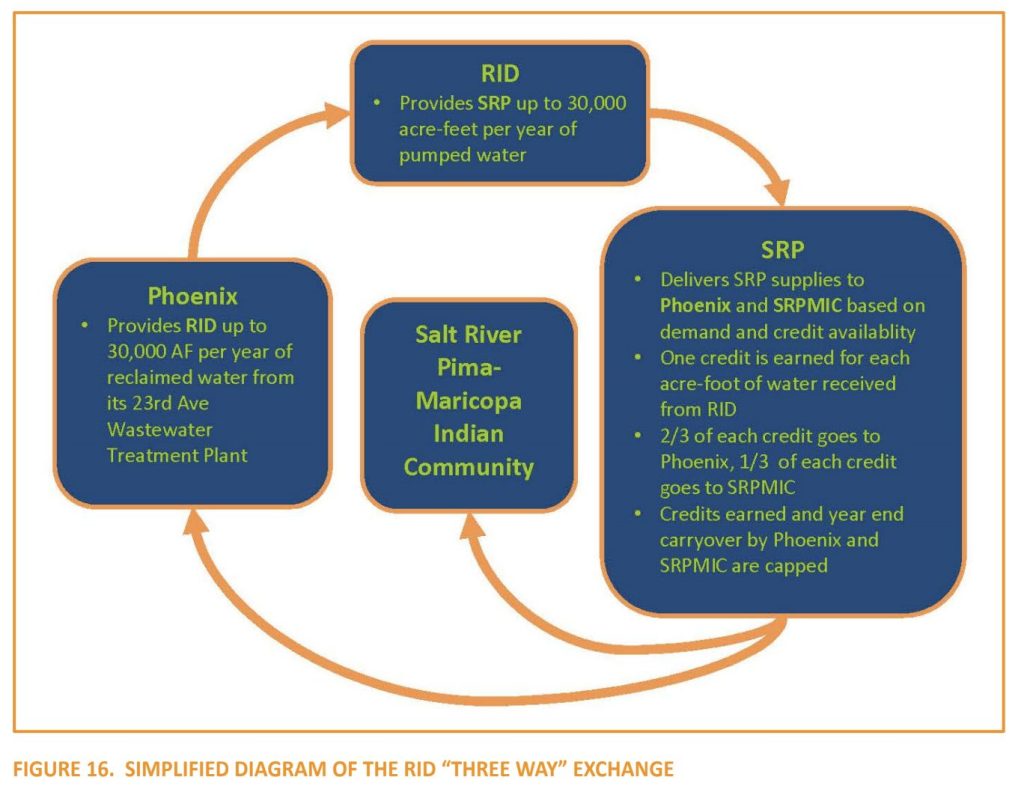

SRP’s system is made up of six dams that can hold over 2 million acre-feet of water. SRP delivers about 700,000 acre-feet of water to municipalities, farms, businesses and residents. Of that amount, the city of Phoenix takes about 20% to 25% of SRP water.

TSMC said in a statement that “approximately 65% of the water used in the Arizona fab will come from TSMC’s in-house water-reclamation system,” which will convert municipal or industrial wastewater into water that can help “reduce the company’s reliance on city water sources.” The statement also said TSMC “has detailed response procedures to handle shortages at different stages and also regularly evaluates new ways to reduce consumption.” In its semiconductor-manufacturing process, “a drop of water is reused an average of 3.5 times, and we will achieve a nearly 90% water recycling rate,” the company said.

City officials said TSMC’s industrial wastewater will be treated on-site, but the city will still have to either dispose of or find a use for a portion that it will receive as effluent. They are still in discussions about the exact amount of water TSMC will recycle on-site. Some of the water the city will receive from TSMC will be injected into the aquifer, which is not an uncommon procedure.

With access to 186,557 acre-feet of Colorado River water, Phoenix injects into the aquifer about 60,000 acre-feet of unused CAP water each year that it doesn’t use, city officials said. Classified as surface water, it could be made available to TSMC.

Sorenson, of the Kyl Center, said the city could benefit from the injection of TSMC water into the aquifer. “Aquifer injection is commonly done here in the Valley of the Sun. You basically take highly treated water and you operate a well in reverse and force that water back into the aquifer… It’s a great way to replenish groundwater that you may have pumped, or just to bolster aquifer supplies.”

Cynthia Campbell, Phoenix’s water resources manager, said that with water a finite and diminishing resource – and Colorado River supplies the first to be affected by climate change – planning for the future will be a challenge.

“What we are facing is a future where at least in part, climate change has played a role with a depleted yield of the Colorado River to the point where we are now going to see probably impactful cuts of water for the Central Arizona Project and, in turn, for the city of Phoenix.

“So, to the extent that you add TSMC to that scenario it becomes a little more challenging, you have to become a little more flexible and really utilize sources of water that we have not had to utilize on a year in and year out basis, and potentially look for new ways to recycle reused water as well,” she said.

In its statement, TSMC said increasing the company’s resilience against natural events such as drought is a major focus of its operation, noting that when Taiwan was hit last year by water shortages caused by the worst drought in more than 50 years, the company “managed to keep operations running without any disruptions.”

Campbell said city planners have factored in shortages of Colorado River water into their water planning, but it becomes difficult if there is a 10% or 15% reduction in supply and a significant increase in demand. “We planned a water supply that would build out the corporate limits of the city of Phoenix, but there’s really no sidestepping the fact that a semiconductor manufacturer uses a volume of water on a per-acre basis that’s far greater than anything we’ve ever seen.”

For its part, TSMC said in a statement that it would “partner closely with the city of Phoenix on water reclamation for our Arizona fab,” noting that the company has “invested considerable effort into building comprehensive wastewater treatment systems and water reclamation systems to reduce both water consumption and wastewater discharge.”

In Chandler, Intel resource managers have been able to easily pump out water they have injected into the aquifer. But in Biscuit Flats, TSMC won’t have it as easy because the area is hydrologically less conducive than Chandler.

“So what Intel is able to do is, they are doing a lot of reinjection and then pumping back out,” Campbell said. “We would like to do that, but for us, it’s a little more challenging because they can do it immediately adjacent to the Intel plant. That probably won’t be possible for TSMC because the geology won’t support it.”

Campbell also noted the extensive regulatory framework regarding how an aquifer can be used, even when water is being put back into it.

Groundwater as a last resort

One thing that TSMC won’t be using is groundwater, Campbell said.

The city enjoys extensive groundwater supplies but views them as a “foundational supply,” only to be used as a last resort. The city uses just 2% of its groundwater supplies, and that amount is used primarily to make sure the city’s pumping system doesn’t become obsolete.

Campbell said Phoenix does have some rights to water from the Salt and Verde rivers that is associated with Salt River Project, but there are no plans to use that water. However, as more fabs are built, those water rights could be accessed by chip manufacturers like TSMC.

Balancing economic development with water scarcity

The benefits of having TSMC and affiliated industries in Biscuit Flats are worth the water-management challenges, Campbell said, adding that state officials shared that view.

“The economic benefit to the city of Phoenix and the larger tax base and the associated folks and the businesses that would come in was significant. I think the state looked at is almost as a game changer – they were very enthusiastic as well,” she said.

Sorenson, of the Kyl Center, said balancing water issues with development in Arizona will always involve difficult decisions.

“I think it is important to remember that literally everything we do, everything we make, every economic activity that we engage in entails the use of water in one form or another,” she said. “I think it is important to understand those tradeoffs, and for communities to understand where their water comes from, where it goes and how to use it to its highest and best purpose. But its highest and best purpose is really going to depend or really vary from community to community, and for the kind of future that different communities see for themselves.”