Nearly every day, in board rooms all over America, executives and their investor relations staff huddle around a speaker phone and put their best collective face on the financial figures they have just filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

With the advent of earnings season, when dozens of such calls are taking place each day, it’s a good time to reflect on the value of this business communication ritual for business journalists.

And “ritual” is the correct word for “the quarterly earnings conference call.” These events have an eerie sameness if you listen to enough of them. Despite their best efforts to sound conversational, executives often come across as stilted or nervous as they read their carefully prepared scripts. Some even have scripts for anticipated questions and have gone through rehearsals with other staff posing as pesky analysts. Investor relations professionals view earnings calls as one of the critical events of their year, so they leave little to chance. (On the website “Inside Investor Relations,” one article details “30 tips for better conference calls,” including “avoid excessive exuberance.”)

The primary audience for an earnings call are the analysts who follow the company for investment banks and institutional investors; these folks are invited not only to listen to the call but also to ask questions at the end of the presentation. A moderator calls on the speakers one by one, so the exchange is far from free-wheeling. But an earnings call can still be mildly revelatory and, thanks to a regulation adopted by the SEC in 2000, anyone else can listen in, including small investors, competitors and journalists.

Regulation Fair Disclosure, or Reg FD, arose to ensure that everyone is able to receive material information about a company at the same time. Prior to its existence, companies might disclose important information selectively in private sessions with analysts or big investors, a practice that put smaller investors at a disadvantage.

If you are a journalist following a particular company, listening in on a conference call should be part of your regular beat responsibilities, just like monitoring SEC filings and insider stock trades. Sure, it’s unlikely that anything unexpected will happen, but you never know.

Perhaps the most infamous – and newsworthy – earnings conference call in history took place in the spring of 2001, when Jeffrey Skilling, then CEO of Enron, responded to a question from a persistent analyst with the epithet, “We appreciate it…a–hole.” Several years later, Al Lord, CEO of Sallie Mae, may have topped Skilling’s gaffe when he ended a conference call by muttering “Let’s get the – out of here.”

Although you are unlikely to hear something as colorful as an offhand expletive, the calls still have value for several reasons:

- You can learn what the company believes are most salient about its filings and develop some context about its strategies.

- You can get beyond the obvious in a quarterly earnings story and provide readers something of value that they are unlikely to seek out on their own.

- You can eavesdrop on concerns informed investors and analysts have about the company during the Q&A session.

- You can hear directly from top executives and quote them in your stories, even if these are people who will never return your call. Simply attribute the comment by saying something like, “the remark was made during the company’s fourth quarter conference call Tuesday.”

- If the executive is someone you plan to interview in the future, you can get a feel for his or her personality, even in a carefully scripted event.

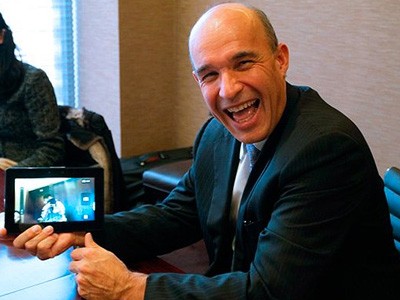

Some executives take pains to be conversational and even jovial. Others are combative and prickly. Referring to a comment made in a conference call when you have that interview can be a good reporting habit. It conveys to the executive that you’ve done your homework.

The vast majority of publicly traded companies have conference calls. It’s easy to find out when they are scheduled by looking at a company’s website, usually under a tab labeled “investor relations.” Some make the time and date available a month or more in advance. Others wait until closer to the call. Many financial sites compile a calendar of upcoming calls, including Yahoo Finance, Marketwatch, Reuters, Seeking Alpha, Earningswhispers.com and Earnings.com.

To listen to a call real time, you often have to complete an online registration in advance via the company’s website. Then you just dial in at the appointed hour and listen. Some companies use technology that allows listeners to view charts and graphs on their computer screens as the call is taking place.

A call usually opens with a moderator or coordinator reading a disclaimer about “forward-looking statements.” Then the CEO typically has a few opening words about the quarter just ended and turns the microphone over to the chief financial officer.

Depending on the news and the company, other executives might be given a chance to elaborate on a particular development or strategy. Finally, the moderator will open the call to questions.

If you miss a company’s live call, don’t despair. A recording is usually archived for a month or so on the company’s website and at financial websites. Some archived recordings conveniently allow you to jump ahead in the call rather than listen to it linearly. Another time-saver is transcripts, many of which can be obtained free from seekingalpha.com; other services offer transcripts for a fee.

Reporters should also review a company’s actual filing of its 10-Q or 10-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission. These filings may take place days or weeks after the earnings press release and conference call — and can contain additional newsworthy information.

Pam Luecke was the initial Reynolds Endowed Chair in Business Journalism; her success at Washington and Lee University paved the way for the naming of subsequent business journalism chairs.