Katherine Eban grew up wanting to be a writer, but not a journalist. Yet fate had a different plan for the now Fortune Magazine contributor.

While working as a policy analyst for the New York City Public Advocate, Eban began doing investigative reports for him on various issues. The reports ended up on the front page of the New York Times.

“It turned out that I was good at reporting and finding stuff, and sort of one thing lead to another,” Eban said.

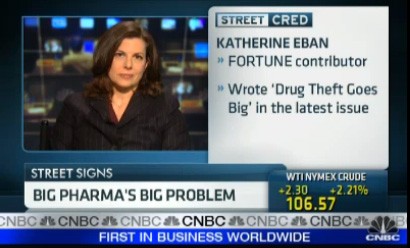

Eban has written for Vanity Fair, Self, The Nation, The New York Times, and the New York Observer. She’s won numerous awards for her reporting on pharmaceutical counterfeiting, gun trafficking, and coercive interrogations by the CIA.

Her Fortune story “Dirty Medicine” won the 2014 Deadline Club Business Investigative Reporting award, and it’s an investigative finalist for the 2014 Gerald Loeb Awards for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism.

Eban took time to talk with us about the importance of fluency in reporting, her experience writing “Dirty Medicine,” and structuring investigative stories. | You can follow her on Twitter @KatherineEban.

1. In addition to pharmaceutical counterfeiting, you also have written on gun trafficking and coercive interrogations. What are some challenges when reporting on technical subjects, and how do you overcome them?

Coercive interrogations is not so much technical subject as that it was a deeply hidden thing that the federal government was involved in and that involved interrogations of detainees. Basically I find that you need to do so much reporting until you basically become fluent in a topic; and once you become fluent in a topic and really have a deep understanding of the issue, then sources are more willing to speak with you. They don’t feel like that have to educate you from the offset.

“If you’re not overwhelmed

by the amount of material

you have, you probably

don’t have enough material. “

2. Your story, “Dirty Medicine,” exposes readers to the criminal fraud at Ranbaxy, an Indian drug company that makes generic Lipitor. How did you even come across such a story?

It was one of those things where I began hearing from a number of different sources that there were problems in the generic drug industry, problems that ranged from poor regulation to dangerous practices. Basically once I started reporting, I kept hearing about the name Ranbaxy. Ranbaxy was sort of the jewel and the crown of the generic drug industry in India. It was a huge company and very prominent, and yet I kept hearing about problems there with what’s known as data integrity.

The drug is the data and the data is the drug, so very faithful documentation of all kinds of test results is the only way you know if you’ve made a safe and effective drug. I kept hearing about manipulation of data, and basically from that point in, I had to give myself a kind of graduate level course on how you make a generic drug. So it was very, very intensive. … It was using the Internet. It was reading, reading, reading. It was interviewing. It was watching YouTube videos on how drugs were manufactured. It was sitting down with experts in the field and offering to take them to lunch if they keep on explaining it to me.

3. “Dirty Medicine” has vivid imagery and expressive dialogue that clearly sets multiple scenes throughout the article. How do you skillfully narrate scenes that you weren’t there for?

Well you try to get input from as many people who were there as possible, and then of course you try to get as much documentation as possible to support that. So I spend a lot of my reporting time trying to get temporaneous notes, emails. A lot of people send emails, “Hey Bob, I ran into Joe the other day, and he told me blah, blah, blah,” I mean those kinds of emails in which somebody documents something effectively and temporaneously. I was trying to get as much documentation as possible, and when you do that, you find that a lot of scenes can write themselves. For example, in Ranbaxy, the “Dirty Medicine” article, in the very opening, what exactly does lobby of Ranbaxy headquarters look like? What are the grounds outside like? When did the gardeners come to work? When the waiters bring tea to the executive, what do they wear? For any physical descriptions, I spent a lot of time looking on YouTube. Ranbaxy wouldn’t allow me to make a tour of the facility; however there was a video on YouTube of the CEO proudly giving a tour to a visitor; it was like a PR video. Wonderful. That can tell me what do the grounds look like, is the floor made of marble or what kind of tile, and all of those are things that can be checked and need to be checked. So there’s a lot of different ways to do that.

4. You went through 1,000+ documents and interviewed more than 40 people for “Dirty Medicine.” What are some ways a first-time investigative reporter can manage an overwhelming amount of information?

Well first of all, the best thing if you do have an overwhelming amount of information, and I think in order to write an in-depth article like that, a real investigative article, you do need to literally acquire that much information.

“it’s very, very time intensive

and time consuming to do the kind

of Excel spreadsheet and outlining

and all of that stuff, but it is

really, really worth it.”

If you’re not overwhelmed by the amount of material you have, you probably don’t have enough material. One thing that I do for all of my long articles is I create an Excel spreadsheet and that’s effectively a timeline. Basically all of the relevant chronology goes into that in a very elaborate spreadsheet of the date, the character, the event, the notes, where I got the information from, and it becomes a kind of template of the article I plan to write. I find that to be very helpful. Let me just say this which is, it’s very, very time intensive and time consuming to do the kind of Excel spreadsheet and outlining and all of that stuff, but it is really, really worth it. There’s almost no amount of time you can spend that’s too much time doing that because it makes article so much easier to write. It’s well, well worth the upfront time investment.

5. For investigative stories, at what point is a journalist capable of explaining things for the reader without citing someone every other sentence?

There are factual things that can be explained about. For example, if there are facts about how you’re supposed to make drugs, the the steps involved, etc. that are not disputed by anybody, those don’t need to be sourced necessarily. But any kind of critical observation about how some company or someone is doing, that absolutely has to be attributed. It is absolutely essential, obviously, to be fair and very sort of ample in allowing everybody who you’re writing about to have a comment, a sort of fair response to what you’re writing, so that is obviously essential. A big part of any story is probably a set of undisputed facts, so those wouldn’t need attribution.