Michael Sallah enrolled in two journalism courses fall quarter of his freshman year at the University of Toledo. It was love at first sight.

“I just went bonkers. I fell in love with it. I knew it was exactly what I wanted to do,” Sallah said.

Sallah also caught the journalism fervor that lingered from the post-Watergate coverage. Journalism appeared to be the melding of his interests in writing, history, and political science.

“You saw the impact of the work,” Sallah said. “…things like that were very appealing to me.”

Sallah’s career has been based on looking into issues that impact people. He worked at the Miami Herald as an investigations editor and reporter for seven years. He is currently on the investigations unit at The Washington Post.

His series “Buried Secrets, Brutal Truths” for The Toledo Blade won the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting in 2004. It focused on Vietnam War crime cases and the Pentagon’s cover up. He and a team at the Miami Herald also won a Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting in 2007 for an investigation into the public housing corruption.

At The Post, he worked with Debbie Cenziper and Steven Rich on “Tax Liens: Left With Nothing,” a series on how tax liens sales affected homeowners. It was a finalist for the Investigative category of the 2014 Gerald Loeb Award for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism. After the story published, lawmakers soon reformed the law to protect homeowners though they didn’t cite The Post’s story as a reason why.

“The watchdog component is important, especially in financial journalism,” Sallah said.

Sallah took some time to talk with us about his experience on The Post tax lien investigation. He shares ideas on how to find multiple sources, present data visually, and handle large projects.

1. Your investigative story “Tax Liens” showed readers the affects of tax liens on homeowners as well as the obscurity of the program. How did you come across this topic?

Like a lot of good stories that come off the metro desk, there was a city council meeting. One day this women got up, and she started crying and talking about how they were trying to take her house for a few hundred in taxes, and we realized there was a problem. It wasn’t just her but others, so we started going to the courts and listening to their cases every Wednesday at 10 o’clock. They had tax lien court. There wasn’t a lot of mercy or sympathy for them from the judges or anyone for that matter. So we realized that was a problem, and we decided let’s launch into it. We found out that some of the biggest companies that were coming in to buy the liens were owned by criminals – owned by people that had been convicted in prior cases. So we were like, ‘Okay, well this answers a lot. We have a system here where basically the biggest spenders here are convicted felons. That’s a problem.’ So we knew we had something here with all those different elements playing out and with people that had gone through tough times that couldn’t pay their taxes, or had difficulty, or had Alzheimer’s, or didn’t pay because they were in the hospital or whatever. Those people shouldn’t lose their homes for a few hundred dollars. There’s something wrong in with a system that allows that.

2. The “Tax Liens” coverage was incredibly in-depth with more of a focus on people and injustice than on taxes. How did you find all of these homeowners who had lost everything? What are some ways journalists can find multiple sources for their own stories?

Steven Rich, who does our computer assisted reporting, managed to be able to find every lien that was sold in the city going back five years. We were able to track the life of those liens, how much they sold for and how many times they led to foreclosures. From there we were able to track it all the way down to the victims, the people if you will.

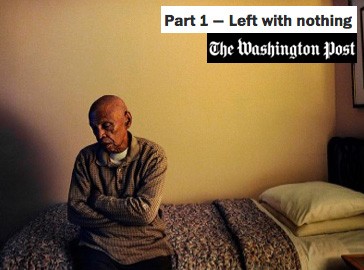

One of the most important things I did in that particular story was … doing the shoe leather reporting. That’s so critical to good reporting. It’s not just about the records; it’s also about going out and finding the people and finding who they were and how they were impacted in their lives. I saw Bennie Coleman and went back to his house several times … until I could actually find him. I had a neighbor actually take me to his boarding house where I found him. At first he didn’t want to talk. He wasn’t real nice. But once he realized we weren’t there to hurt him, then he opened up, and we were able to get this poor guy’s story. Former Marine who had served in Vietnam, and he loses his house over what started as a $134 bill. He has Alzheimer’s. He forgot to pay it. It’s just a disaster in the way in which he lost it, and that was a big part of our story is what kind of system would allow those types of unfortunate events to even happen to people. It is a combination of drilling down, being effective, getting the records and being able to quantity information from the records — how many were sold, for how much money — and really be able to get a birds eye view on the story by doing that kind of massive computer assisted reporting … and then also taking it home and going out on the streets and again, knocking on doors. It’s all very important.

3. “Tax Liens” had vivid photographs and informative graphics as well as maps that helped illustrate what neighborhoods investors were targeting. At what point did you start thinking of designs and graphics? When should reporters start thinking of how to visually present the data?

You should start to think about it right away. You don’t have to do anything right away, but if it’s a project … you need to meet with your projects people, the people that do graphics and the photography and the videos, and we did that. We got them on the ground floor very early and out once we identified the story. Then we started meeting with them right away so they could help in the preparation. Sometimes they think of things that we don’t think of. They’re an extra set of eyes and ears out there. But you should do that very early on so that you can kind of work together and help collaborate so it’s not all coming at the last minute. You don’t want that.

“We found out that

some of the biggest companies

that were coming in to buy the liens

were owned by criminals.”

Michael Williamson, who shot all our stuff, he’s a great photographer. I worked with him a lot on this. We went out several times, and I tried to get things set up, but sometimes they’re not perfectly set up. So he has to go out and do these, I call them coyote runs, where you’re just going out there and just flailing and hopefully you come back with something. Sometimes you do, sometimes you don’t, but those sometimes lend themselves the best photos in stories because they’re totally unprepared and you get people before they have a chance to say no. Those are some of the things you have to do. You can’t sit at your desk and do stories. You’ve got to get out, and they did. Our videographers went out and so did our photographers, even our graphics people went out at times with us to talk about it, conceptualize things we’d need to explain the story.

4. You worked together as a team for 10 months on this story. Were there any challenges that come with group reporting versus individual reporting? What advice would you give to an investigative team on handling multi-faceted projects?

There always is. Every time. Sometimes you bump into each other. Sometimes one person wants to do the same thing, but we worked it out. There’s always going to be creative conflicts that go on, but none of them are personal … they just happen. We’re both high charged reporters, Debbie and I, and we’ve worked together off and on for 10 years. We worked at the Miami Herald, and so we knew each other well enough. But still you run into situations where one person may feel like they’re running out in front of the other one or getting ahead or whatever it might be, and it can create sometimes some sort of misunderstandings. Those usually work themselves out pretty easily, but it does happen.

“You have to take the responsibility

as a reporter to make sure that

good video is shot,

that good photography is shot.

You can’t do it yourself.”

I think you need to remember that the content is critical. You’ve got to make sure you divvy up the work right. It’s always a good thing to set off a project together, where you all try to say, ‘hey look, we’re all equal partners in this, and it’s really about the story, not about us.’ Try to do that. You should communicate every day with the most important people on the project. In terms of where you have a lot of different multi-platforms stuff going on … it’s always on the reporters. At the end of the day, they’re the ones driving it and maybe their editor. You have to take the responsibility as a reporter to make ensure that good video is shot, that good photography is shot. You can’t do it yourself. You can make sure they have the best opportunities to do it. It falls on the reporters, not the photographers, not the videographers, not the graphics people. They rely on what the reporters give them. It’s always a challenge. It’s a lot of juggling. It’s worth it though, for any reporter to think along the lines of making sure that all platforms met because it only makes your project better. The first day I think we got 4.5 million hits. I mean it was amazing. That really quite stunning, and it was because of all those elements of good photography, the good writing, and the good presentation. The graphics were phenomenal. When you have that kind of level of excellence, you’re always going to get something good. I mean, tax liens is not an interesting topic. We had to try and make it interesting.

5. You’re both an award-winning investigative reporter and editor. How has experiencing both positions helped your writing? When working together on a story, what are some misunderstandings or challenges that may come up, and what can an editor or reporter do to fix that?

I think you have a greater appreciation for presentation. Most of my editing was actually at the Miami Herald. I was the investigations editor there, but I did both. I think what it allows you to do is have an idea and keep that idea and stay true to the vision of the story. I think that helps a lot when you’re an editor. I think it helps with the writing and the reporting because you can appreciate a reporter that comes through for you when you’re an editor on several different levels. You know the breadth and the scope, you know the depth at which they had to go and get that. So when you’re reporting again, you’re going to want to do that for your editor, whoever is editing your story, and show the same level of competence that somebody else showed you as an editor. It works back and forth. I think it makes you a better writer in the end too. You’ve had to save stories. You’ve had to go in and rewrite them.

Sometimes there’s differences in how you approach something, and that can happen, but most of it is all ego. Most of it is, ‘This is mine. No it’s mine. No, it’s mine. No, it’s mine.’ It’s very ego driven. A lot of it too is you get highly charged when you’re reporting so you tend to clash because it’s your work, but it’s their work too and you have to recognize that. It’s a melding of the two that you get your best stuff because both of you contributed and then you take the synthesis of that.