Detroit is an endlessly fascinating topic. Its rise and fall is an American tragedy, while its slow ascent back to normalcy has drawn the attention of historians and urbanologists.

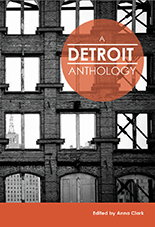

Although plenty has been written about the city, much of it has been by outsiders. A Detroit Anthology is different. It is stories, art, poetry, and photographs by Detroiters about Detroit.

The editor is Anna Clark, a freelance journalist whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, The American Prospect, Grantland, on NBCNews.com, the Columbia Journalism Review, and other publications. She is the founder of Literary Detroit and can be found online at www.annaclark.net and on Twitter @annaleighclark. In the first of a two-part conversation, we spoke with her about the philosophy behind the book, the latest offering in our Win This Book series.

1) A Detroit Anthology is part of a growing collection by Belt Publishing. Please tell us how it came to life.

The suggestion came from Anne Trubek at Belt. She’s doing wonderful things in building Belt Magazine as a source of journalism about a region of the country that is often overlooked and simplified in major national news outlets.

(She) had success in publishing an anthology about Cleveland, and got to thinking about other cities rich in stories: Cincinnati, for one, and Detroit for another.

As journalists in the Rust Belt with similar interests, Anne and I were familiar with each other, so she reached out and asked if I’d be interested in editing the Detroit book.

2) The book truly is an anthology — there are essays, poems, photographs and art. Why go that route, rather than traditional reportage? What is the common thread that connects all these various pieces?

Some of this came about organically: I didn’t list poetry on the original call for submissions, but so many writers nudged me about it, pointing out that heated poetic language was the best way for them to translate their particular experience with Detroit.

I’m a journalist, and of course I’m partial to reportage and essays. But I hardly believe that the medium is the only way to communicate truth. In fact, if this was going to be an honest book, I felt that it needed to embody the multiplicities of this city, and not just explain them. I didn’t want the anthology to feel unduly disjointed — and for that, I was attentive to the proportions of the pieces, and their ordering — but I did want it to have room in the book for the diversity of expression that is born in Detroit.If there’s a thread that connects it all, I’d say that it comes down simply to the contributors wrestling as honestly as they can about a resonant aspect of their Detroit experience. The pieces (even the reportage) are personal.

3) There is a lot in the book that doesn’t follow the conventional wisdom about Detroit. Tells us about some of the pieces that break from that norm.

It was fascinating to see what kind of stories people wanted to tell, when given an open invitation. Turns out that wisdom didn’t come in just one kind of box.

“Fort Gratiot” details the story of a hardware store owned by the author’s father. As the city becomes more difficult, the owner doesn’t move to the suburbs during white flight, like many of other shopkeepers. He does, though get increasingly intense about protecting the shop.

Other pieces — like “The Kidnapped Children of Detroit,” “Turner Ronald Carter the III” and “When the Trees Stop Giving Fruit” — put a lens on neighborhood integration, and the ensuing flight of white families out of the city.

As the authors describe their experiences, it was emotionally painful, and a devastating blow for their home neighborhoods, many of which never recovered. Their stories reveal how this downward spiral was ignited in the 1950s and 1960s, when the auto industry was still on top of the world.

4) You’ve won a Fulbright Award, and you’ve worked for major national publications. In 2012, you founded a Detroit literary group. How has your past experience prepared you for what you did here?

I think straddling a lot of different communities helped me bring a broad acquaintance to the project, which was useful in distributing the call for submissions, recruiting key voices to the book, and being attentive for glaring absences in the draft manuscript.

Also, with my day-to-day work, I’ve had to learn to be organized, be unafraid to work hard, and be pretty comfortable with independent projects, all of which turned out to be essential as the preparation of the anthology shifted into high gear. I’m also a big-time reader, which teaches you all sorts of things through osmosis that came in handy, like having some sense for narrative flow.

Finally, whether it’s pitching freelance articles or getting people excited to come out to Literary Detroit events, most of what I do has a sort of entrepreneurial beat to it. That was helpful experience in working to get the book in people’s hands, and being able to bring some game to events that feature the anthology.