When the Star Tribune’s Chris Serres began exploring the fast-growing home health and personal care industry in Minnesota, he was investigating fraud in Medicaid payments. What he found was rampant chaos and neglect. His and data editor Glenn Howatt’s work exposed the weaknesses in Minnesota’s home-care industry and its regulators. Their reporting, in the story “Unchecked Care,” earned the team the 2015 Silver Barlett & Steele Award.

Here’s how they conducted the investigation.

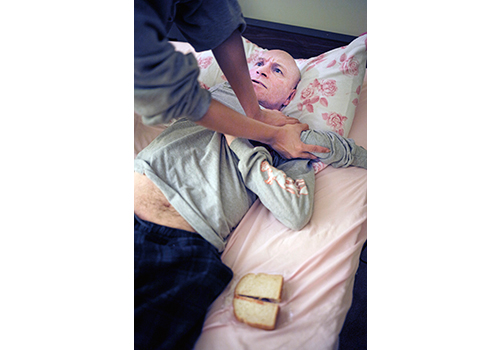

The state’s largest home care agency had quietly imploded and eventually filed bankruptcy. Many employees walked away from the clients they were supposed to care for because the company had stopped paying them. Patients on ventilators and feeding tubes felt abandoned. Other workers showed up when they could, although they often didn’t have the money to pay for gas to visit their clients.

Even though state officials knew that the company was failing, regulators failed to step in and find new sources of care for the firm’s 1,000 clients, who were often left without assistance for weeks at a time.

Often referred to as a “care system without walls,” home health and personal care is held out to be the future of health care. It offers the promise of letting patients heal at home and allowing the disabled to stay in their communities, rather than housing them in costly hospitals, nursing homes and residential institutions.

When Star Tribune reporter Chris Serres began his work with data editor Glenn Howatt, there was no extensive paper trail of regulatory surveys, inspections or complaint investigations.

Using the historic Medicaid enrollment records, however, Howatt discovered that the collapse of the state’s largest agency was not unusual. Of the 800 agencies that were enrolled with the state in 2009, one-third had shut down by 2014. State labor department records also showed that more than 100 home-health firms had more than $350,000 in unpaid-wages claims going back five years.

Also, unlike the rest of Minnesota’s nonprofit health care industry, home care agencies were primarily private companies that had little oversight by government agencies.

Lacking a detailed document paper trail, Serres relied on court records and a network of current and former agency employees, patients and patient advocates.

His reporting showed that as home health care has grown, its patient population has become sicker with more complex needs. But training of care aides is almost non-existent. The only barrier to entry is a brief online quiz with questions such as, “When talking to a 911 operator, do not hang up. True or false?”

Many aides perform complex procedures like inserting feeding tubes and cleaning infections to monitoring intravenous fluids. Faced with complex problems of clients in urgent need, most felt they had no choice but to perform tasks that were supposed to be done by a licensed nurse.

The reporters relied on the state’s Commerce Department, which regulates franchises. The home health industry in Minnesota increasingly resembles the fast food industry, run by owners who have little or no health care background. Regulatory filings showed an industry that had an intense interest in marketing, including a few firms that had cozy arrangements with placement firms to refer patients.

Serres’ and Howatt’s reporting shed new light on the practices of an industry that is now deeply ingrained in the personal lives of elderly Americans, and they held state regulators accountable for their failures to protect these vulnerable citizens and their families.

Their work has also caught the attention of elected officials. The series prompted state regulators to accelerate the use of background checks on home-care aides and to intensify their monitoring of financially troubled agencies.