In the 20th century, a fair chunk of advertising appeared in newspaper columns and between TV news segments. The news publishers captured that revenue, and their bottom lines boomed.

Today, that same advertising appears between posts in the endless scroll of videos on TikTok and Instagram. Many of those posts might be published by news outlets, but the news publishers are no longer seeing the revenue.

To stay ahead, news organizations are repackaging their reporting into short-form videos formatted for mobile phone screens. And while some have had great success in reaching new audiences on vertical video platforms, they’re yet to find much revenue.

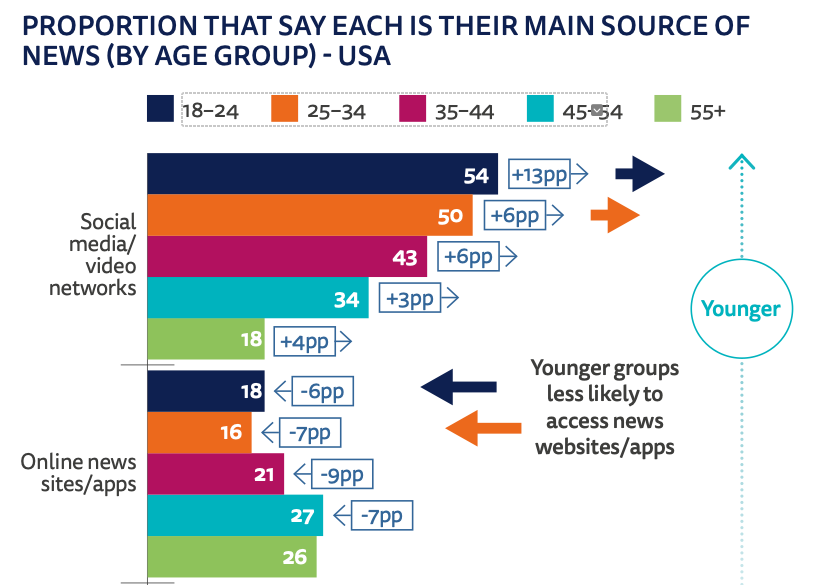

For the first time, this year’s Reuters Institute Digital News Report found that a majority of Americans under 35 use social media and video networks like YouTube as their predominant source of news. And short-form video’s growing influence in other fields is undeniable: it’s hard to imagine outsider candidate Zohran Mamdani winning this year’s New York Democratic mayoral primary without also providing a masterclass in political storytelling on TikTok.

This might not be all bad for the public’s access to information. A surprising quality of nuance and diversity of viewpoints can fit into a three-minute video, and Instagram reels from traditional news publishers like The New York Times often take a similar form to reports heard on radio shows like NPR’s All Things Considered.

But that attention is coming at the cost of eyeballs on news publishers’ own websites and apps, where they can be directly monetised through subscriptions and advertising impressions. With short-form social video, publishers’ content is appearing on platforms over which they have no control, leaving all the keys to revenue in the hands of the platforms themselves. The financial opportunities for publishers are comparatively meager, no matter the journalistic quality. And while many publishers are following their audience onto these platforms, it remains unclear whether there is a pot of gold at the end of the Instagram rainbow.

TikTok’s Creator Rewards program pays 40 cents to $1 per 1,000 views, but eligibility is restricted to “personal” accounts, excluding the “business” accounts used by most publishers. On Instagram’s Reels, meanwhile, there are no direct compensation programs.

Articles addressing how to make money using Instagram Reels recommend that accounts use Instagram’s paid subscriptions feature, which locks content behind an in-app paywall; promote their own products and merchandise; or produce paid partnerships with brands — suggestions that would either harm publishers’ existing subscription models or enter ethical territory that most are unwilling to cross.

This leaves news publishers in a difficult strategic bind, placing their mission to provide quality information to a broad public audience in conflict with their need to make money: money used to fund the reporting, editing and fact-checking essential to good journalism. Publishers can either invest in these platforms in the hope of reaching new audiences without any guarantee of financial returns, or stay out of the field and allow potentially less scrupulous ‘news influencers’ to fill the information void.

To understand how publishers are navigating this dilemma, The Reynolds Center contacted more than ten news publishers across print, digital, radio and TV news who are either currently publishing on short-form social video platforms, or actively hiring for social media video-oriented roles. Though several declined to speak on the record, citing company policy on discussing internal strategy, the picture that emerged is of a news industry following audiences onto these platforms, while hoping the revenue will come later.

“It was never set out to be a money-making device,” says Carin Leong, a documentary filmmaker and social video producer at Scientific American. Two years ago, Leong and a small team began producing short-form videos for the magazine’s social media accounts, which have since grown to over a million followers across Instagram, TikTok and YouTube.

At 180 years old, Scientific American is America’s oldest, continuously running magazine, and has an elderly audience to match, says Leong. “We had a legitimate problem of losing subscribers because their kids would call us and say, ‘Hey, my dad died, can we cancel the subscription?’”

The social video project “enabled us to reach a much younger audience,” says Leong. “It’s now a 50-50 split between men and women, a lot of people between 18 and 35.”

However, Leong is aware of the difficulty of converting that audience into a paying readership and the limited direct revenue options available on TikTok and Instagram: “The platform is built for you to do this,” she says, miming an endless vertical scroll, “and not click through to a website.”

Instead, “it’s a brand awareness thing: We’re slowly chipping away and making ourselves more prominent to younger audiences with the hopes that maybe in five years or 10 years or in 15 years you might want to subscribe.”

Only time will tell whether a generation trained on 90-second TikTok videos can be converted into paying magazine subscribers. Like many legacy titles, Scientific American appears to be under financial pressure today. In July, senior editor Jeffery DelViscio posted on LinkedIn, “We could fail without support. If you want to see SciAm survive, please consider supporting the work that we’re doing here.”

“What I will say is that there is money in audience,” Leong says, pointing to “underwritten” deals in which an advertiser will pay for the publication to produce a series of stories on a specific topic with varying amounts of editorial oversight. Leong clarified in an email that short-form social video has yet to factor into a deal like this at Scientific American, but previous deals have incorporated longer videos on YouTube.

Leong also worries about the medium’s effect on journalistic integrity and nuance, fearing that “any kind of algorithm-fuelled storytelling will always fall into the pits of hot takes and exaggerated statements.”

Yet this fear also represents the societal hazards of ethical news publishers staying entirely away from social video: if nuance and complexity are not available in the arenas audiences are flocking to, Leong’s fear may be destined for reality. A recent New York Times article quoted a TikTok user who had posted a video calling hormonal birth control “evil” saying, “Obviously I exaggerate … on social media you can’t have a lukewarm take.”

Instead, in one of Leong’s recent videos, she cuts halfway through to say, “Well, it’s more complicated than that,” before explaining the limitations and caveats of an exciting new study. Comment sections on Scientific American’s videos are often filled with thoughtful, multiple-paragraph responses.

Developing the vibrant and friendly yet still rigorous voice of Scientific American’s vertical videos required senior staffers to give Leong’s team enough time to experiment. “If you scroll all the way back, you’ll see some things that worked and some things that didn’t work,” says Leong, adding that some of the early videos may have leaned slightly too heavily on humor. “Over the course of time, we’ve narrowed down to this one voice that has worked for us.”

In the experimental TikTok arm of one of America’s most storied newspapers, humor was the point.

In 2019, David Jorgenson launched “Washington Post Universe”, quickly gathering a large audience on the back of short-form video coverage of the daily news cycle in the form of sketch comedy seasoned with the vocabulary and aesthetics of internet memes. Jorgenson became known in the industry as “the TikTok Guy.”

This July, Jorgenson left the Post to set up “Local News International” (LNI), taking with him the Post’s head and deputy head of video and two Post producers. (A senior social media strategist at The Washington Post declined to comment for this article, writing, “our strategy is still taking shape.”) Much like Washington Post Universe, LNI publishes comedic takes on the daily news, as well as two weekly newsletters.

Freed to operate under its own business model, the new venture’s early strategy reveals the difficulty of turning short-form video viewership into revenue. Instead, LNI is selling paid memberships providing access to quarterly Zoom Q&As and a private Slack channel to chat with Jorgenson. In other words, the journalism is given for free and subsidised by those willing to pay for access to the personalities who produce it.

LNI is also offering “Media Strategies,” fronted by the two former Post video heads, Micah Gelman and Lauren Saks. This media consultancy service includes “platform-specific growth modeling to build reach, revenue and relevance for your brand,” and “expert resource sizing to build skilled and efficient teams.”

This consultancy model might be familiar to readers of design magazines: since 2017, Apartamento magazine has run Apartamento Studios, a branding agency providing art direction and creative strategy to clients including Calvin Klein, Nike and H&M. Cult lifestyle and design publication Monocle shares a parent company and cofounder with Winkreative, a branding agency working for property developers, ski resorts and luxury car brands.

These relationships have mutual financial benefits as the “cool factor” of the magazine creates demand for the consultancy services, which in turn subsidise the magazine. But it has profound implications for journalistic integrity, raising questions about whether the magazine would truthfully cover a company that they suspect to be a potential consultancy client. Local News International did not respond to a request for comment.

One corner of the media industry where short-form social video poses less of a dilemma is at non-profit outlets, where the mission to publish great information to the widest audience might be weighted more heavily than the pressures of a quarterly business cycle.

“The biggest instigator for us is: How do we as journalists serve people every day who need information?” Sam Van Pykeren, a social video producer at Mother Jones, tells the Reynolds Center. “We take the approach of short-form investigative documentary,” he says.

This result is rigorous fact-checking, legal review, and storytelling brought to a younger, more diverse audience in a more accessible form. Mother Jones’ videos regularly receive hundreds of thousands of views across platforms, and “every time we see a video go really well on TikTok or Instagram, our audience expands in ethnic demographics, geographic demographics and age demographics,” Van Pykeren says. “These are people who are not subscribing to a magazine. These are people who don’t even know that we have a physical magazine.”

Like Scientific American, Mother Jones’ success in social video is in part the result of a softening in the relationship between publisher and audience. “It’s not just making a piece and having it do well,” Van Pykeren says. He and his two colleagues on the social team regularly engage with commenters “to really encourage…personability between the commenter and the organization account.”

Mother Jones has also worked with third-party creators to produce videos for their accounts. In January of 2024, the magazine hired Garrison Hayes as a video correspondent. Hayes makes fast-paced, sharply-produced analysis videos for, recently interviewing Barack Obama. In July of that year, Mother Jones also hired Kat Abughazaleh as a video creator, who has since left the publication to run for Congress with a campaign heavy on short-form social videos.“It’s a very, very symbiotic relationship,” Van Pykeren says of Hayes. “We give him newsroom resources, fact-checking, edit structure, support to go and pursue things that he wants to do. And in turn, we’re getting incredible journalistic video content from him.”

And Van Pykeren says there is some evidence that Mother Jones’ success on social media is translating back into revenue. “Every time we see a post do really well, we’re seeing new donations,” a trend his team is hoping to enhance by putting “more of that language into our videos.”

Some see a clear answer to publishers’ social media predicament: compel the tech companies to pay for the attention and ad impressions news content brings to their platforms.

TikTok owner ByteDance generated $155 billion in revenue in 2024, while Facebook and Instagram owner Meta generated $164 billion. In 2023, two Columbia University academics estimated that Google and Meta owe a combined $14 billion a year to U.S. news publishers for their content, or about two-thirds of the U.S. newspaper industry’s total annual revenue.

In recent years, both Canada and Australia have passed laws requiring tech companies to enter bargaining agreements with news publishers for their content. In Australia, parts of the law were modeled on the bargaining process used in TV sports licensing deals, explained Allan Fels A.O., who chairs the Australian Public Interest Journalism Initiative and served as the country’s leading competition regulator from 1989 to 2003.

The bargaining approach is “problematic,” Fells said, “because the two parties have completely different estimations of what the price should be.” The law was complicated by trying to define journalism as a unique “public good,” and today, “there’s hardly any money going in.”

“We need some sort of redistribution,” said Sacha Molitorisz, a senior lecturer at the Centre for Media Transition in Sydney, and “I’d argue for it to be as simple as possible.”

In longer-form online video, YouTube has split advertising revenue with nearly all video creators of a certain moderate audience size for decades, regardless of whether it’s news or anything else. Since 2013, 55% has gone to the video’s creator, and 45% to YouTube. Not only has revenue sharing allowed established news outlets to see a return from publishing on the site, it has also allowed for entirely new journalism startups to emerge. One such startup, TLDR News, received £376,000 from its 172 million YouTube views last year, and made more than £1 million overall.

Whether or not this model is suitable across the online media landscape, Molitorisz is uncertain. But, he said, “I hope there’s some momentum that keeps going to work out a solution for this redistribution.”