Our popular business beat basics series is now available all in one place in ebook form for your convenience. Go here to download the Reynolds Center’s free ebook, Business Beat Basics.

***

FINANCIAL BASICS

A full course in finance is beyond the scope of this guide. But for those new to examining a company’s financial statements, a few basics may be helpful.

The core of a company’s financial statements consists of four parts: the balance sheet, income statement, statement of cash flows, and statement of comprehensive income. They offer investors and others four ways to weigh a company’s health and operations.

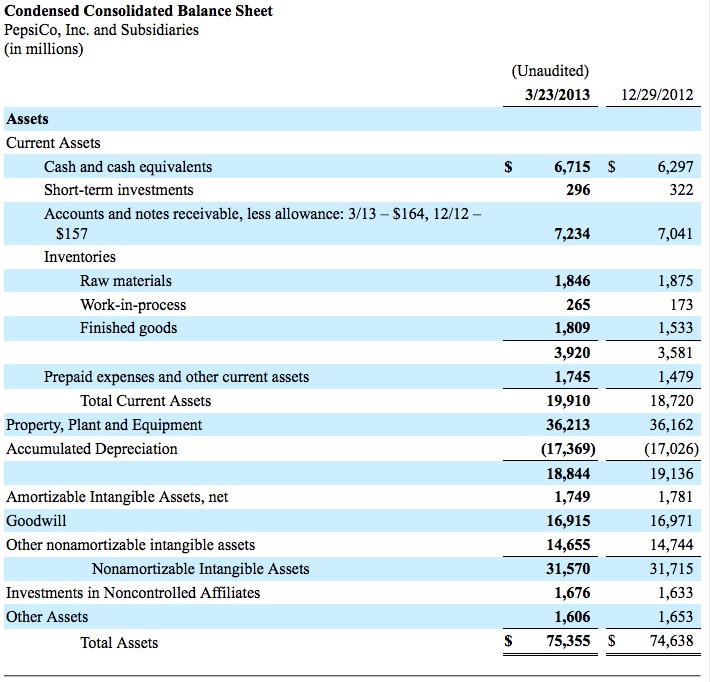

THE BALANCE SHEET

The portion of Pepsico’s balance sheet shows that nearly half of its assets consists of property, plant and equipment; nearly $4 billion more consists of raw materials and inventory.

A balance-sheet is a snapshot of a moment in time: where the company’s books stand at the close of business on a specific day — the last day of the quarter (or year). It doesn’t tell you much about what happened over the course of the quarter, unless you compare it with a previous balance sheet.

ASSETS AND LIABILITIES

It’s divided into two main parts: assets and liabilities.

Assets are what they sound like — cash and other investments and what’s sometimes called property, plants and equipment (or hard assets), as well as intangible things like intellectual property (patents, brand names) and goodwill, an accounting construct that represents the difference between the market value of an acquisition and what the buyer paid for it. (See the Glossary.)

Current assets are generally cash or “cash equivalents” (e.g., short-term bonds) that can be liquidated quickly; investments (other, longer-term financial assets); property, plant and equipment; and other (a catchall category).

Liabilities are also mostly self-explanatory: Many are debts. Some are straightforward financial debts, such as loans taken out from a bank (or several banks at really big companies). Other liabilities are more abstract, such as a company’s liability for its pension plan, which represents the promise to pay workers and retirees specific amounts in the future.

Accounts payable include all the bills a company owes but hadn’t paid as of quarter-end, perhaps for raw materials used, as well as income or other taxes due but not yet paid, this week’s wages (which will go out with next week’s payroll), etc.

As with assets, liabilities are generally categorized as current (due within a year) or long-term. As time goes by, a given liability shifts from a long-term liability to a current liability — for example, as a loan nears maturity.

Debt in itself isn’t bad — even healthy companies flush with cash may take on debt. But sudden increases in debt can be a sign of trouble (or of an impending acquisition).

STATEMENT OF SHAREHOLDER’S EQUITY

This is sometimes called “owner’s equity.” Think of it as the company’s net worth: assets minus liabilities. In theory, it’s what shareholders get if the company liquidates (though liquidations tend to be more complicated than that). Shareholder’s equity breaks down into different categories — common shares (what you normally see traded in the stock market), preferred shares, and also categories such as retained earnings, which is what it sounds like: profits accumulated over the years (minus dividends already paid out to shareholders).

Shareholder’s equity is an important concept for investors. Among other things, it gives a sense of how successful a company has been over time. That said, it rarely comes up in journalism except in columns about stock investing and occasionally in merger and acquisition news.

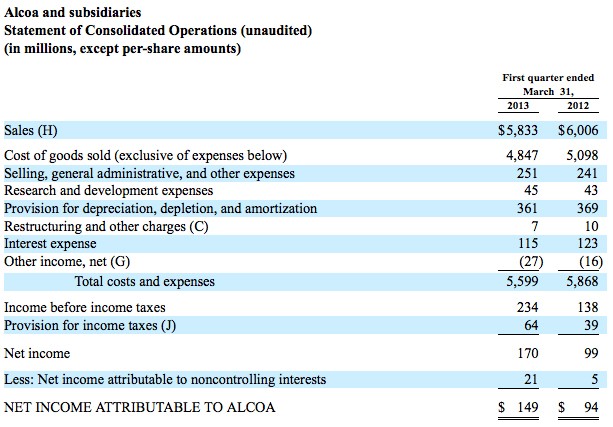

THE INCOME STATEMENT

The bottom line: Sales, expenses and net income at Alcoa, comparing first-quarter 2013 to first-quarter 2012.

If the balance sheet is a snapshot in time, the income statement – also called the profit-and-loss statement, or P&L – is more a summary of (financial) events over the prior quarter.

Most companies sell products or services, generating revenue in the process. You’ll see terms such as “gross revenue” and “net revenue” (sales before and after discounts, respectively), but revenue roughly amounts to a company’s sales for the quarter (or whatever period is covered by the income statement).

Revenues are offset by expenses — what it costs to run the business, from keeping the lights on to salaries and benefits. “Cost of goods sold” counts whatever goes directly into producing the company’s products and services, including raw materials and labor (wages).

Operating income is roughly what the company makes from its actual business – selling burgers, cars or consulting services, for example. It excludes things such as taxes, interest paid to lenders and stakes in joint ventures or outside companies.

Those excluded elements are included when it comes to net income, the infamous bottom line (because it typically appears near or at the end of an income statement). Net income measures profits.

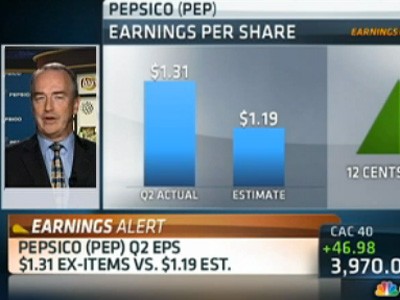

Earnings per share is simply net income divided by the number of shares outstanding.

THE CASH-FLOW STATEMENT

Be careful: Revenue doesn’t necessarily mean cash in the door, and companies can’t always take profits to the bank. That’s because cash and income are different when it comes to big-company accounting. (Very small companies often function on a cash basis.)

Here’s one way to think of it: If a company closes a big sale to a customer on March 31, it can count as revenue even before any cash reaches the company’s bank account. Moreover, the company will record an expense for, say, a power bill at a plant for the first quarter even if it actually cuts the check to the electric utility once it receives the bill in April.

Cash flow breaks down into four areas:

- Cash from operating activities, which is what it sounds like;

- Cash from investing activities, including long-term securities portfolios or real estate;

- Cash from financing activities, which includes dividend payments and stock buybacks; and

- Supplemental information, typically taxes and interest paid.

Some investors rely heavily on cash flow, seeing it as a more reliable picture of a company’s activity.

A WORD OF CAUTION

Technically, the financial statements in a 10-Q aren’t quite as robust as those in a 10-K (annual report) filing. That’s because the 10-K must be audited by an outside accounting firm, while the 10-Q is simply “reviewed” — a less rigorous standard.

It rarely makes a difference, but it’s worth keeping in mind: If a company’s management wants to cut corners or push the envelope on managing the books, it may be a little easier to do so in quarterly reports.