Sonari R. Glinton was searching for a job after a company he was with laid-off employees following 9/11. He and his colleagues were offered help with their resumes as they looked for new jobs. One work session involved creating a dream board of jobs they thought they’d like.

Glinton’s board contained words like “literary, journalism, reporter, producer.” They were reflective of his past, his involvement in his high school and college newspapers.

“I didn’t think it was a thing I could do. Other people did it, but I didn’t. And it took me about however long after college, after a really traumatic event for the country, and being laid off for a while to realize ‘Oh, I want to be able to do that.’ “

Glinton was offered his first news internship when he was 30 years old. Interning for free at member station WBEZ in Chicago was challenging, but it helped him get his foot in the door.

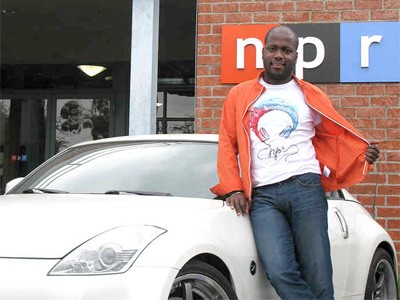

He produced and reported for WBEZ. Glinton joined NPR as a producer for All Things Considered in 2007. In 2010, he moved to be a Business Desk reporter at the NPR West bureau. He focuses on consumer goods and behaviors, as well as the auto industry, marketing, and advertising.

The Chicago native took time to speak with us about keeping audience’s attention, structuring stories for audio, and being yourself on air.

1. Radio obviously doesn’t contain that visual component that print and online publications use to attract viewers. How do you try keep an audience’s attention for business stories?

Most people listen to NPR when they’re doing what I’m doing – commuting. I have a relatively new car so I can choose between Spotify, the news, you interrupted the President on KKJZ, making a phone call to my mother, there’s a lot of things that can happen. I think one of the things we’ve been learning is that you’ve got to give … it’s such a cliché … but you have to give people reason to care. You have to give them a character or a real reason to tune in, not to tune in, to stay in.

You have about 10 seconds where people are going to be like, ‘Nah, I don’t care about this subject’, then you have about a minute or so where people are going to assess whether or not they’re going to listen. I think we’ve been learning at NPR recently, especially grabbing for that first minute and giving them compelling characters, or compelling voices, or some really interesting information in that first minute is vital.

We’re relearning it, but it probably goes back to the caveman days. If you don’t got them in that first minute, you don’t have them at all.

2. Some of your pieces have background noise while others do not. Is there a reason for that? How do you determine when to use natural sound?

You know, we strive for sound enriched storytelling because it helps bring you to a place. Because making a radio story is sort of like making a little movie, but the thing is, you see the movie in your head. So if I provide the character and the sound and the details, you can fill in the little movie that’s playing in your head. If I have to do a piece on General Motors on Capitol Hill, there’s not a lot of interesting sound. I mean, how many times can we use a gavel in my career? There’s only so much.

The way newspaper journalists have word constraints, we have time constraints. I may have to tell a story in four minutes. Sometimes it’s worth it to spend 10 seconds hearing me walk through a theater in central Minnesota because it tells you something, but sometimes maybe it won’t. In the best of all worlds, I’d have some sound element, some real person in my story. The stories that don’t have those things usually mean I was overly rushed and was trying to get something on the air for something that was coming fairly soon.

“A radio story is a lot like a bar story. You go to a bar, you’re talking to a friend, and you’re like ‘Hey this thing happened today where the CEO of GM was on Capitol Hill and she was with her blah, blah, blah.’ That’s part of how we talk to each other … “

3. How do you structure an audio piece? Do you plan ahead for sound bites?

Well as a little background, I’m a journalist clearly, but I got trained as a show producer for All Things Considered … I think I approach things a little differently than say someone who was started in print. When I plan out a story, I think who might the interesting characters be before I go, who might I want to talk to. Then I think, what’s the sound that I can capture. If I’m going to go to talk to a car dealer, do I want to talk with him in his field office? Or do I want to talk with him in the middle of the parking lot? What’s the best case scenario? I think I’m looking for that before I go into an interview, and I almost always go in with my recorder on and rolling by the time I get out of the car. Even if I’m just going to sit down in someone’s conference room, maybe we’ll pass someone in the hallway, or maybe they’ll want to show me something, and even that little bit will give somebody an insight into a world they may not see.

4. I hear from a broadcast standpoint that video packages should last more than 2 minutes, but some of your audio coverage goes past that. How do you decide on the length?

That’s part of the news judgment, ‘Do we need to do this twice?’ Do we need to do four minutes? Maybe I found some funny, interesting thing that will hit it home. Maybe I’ll talk to some guy that has an interesting voice. That may make it longer, but if I can only talk to people on their phones or whatever and the sound’s not going to be great … then it might be much shorter than something that has a scene. It really depends. If I’m doing a profile on a guy who has a rich and interesting story, it’s likely going to be on the Planet Money’s podcast.

That gives me 22 minutes and then I’ll do a shorter version on the radio that will be probably let’s hope seven. But my normal stories cover between 3.5 minutes and 5 minutes.

“I almost always go in

with my recorder on

and rolling

by the time I get

out of the car.”

The way I think of it is, a radio story is a lot like a bar story. You go to a bar, you’re talking to a friend, and you’re like ‘Hey this thing happened today where the CEO of GM was on Capitol Hill and she was with her blah, blah, blah.’ That’s part of how we talk to each other, at NPR, when you see the person’s eyes go down, then you say, ‘Oh, but then there’s this other thing’ … and you start developing the beats and keep the people interested. If I can tell it to someone that means I understand it. So when I sit down to write, it sort of flows out: and then this happened, and this happened, and oh my goodness, I don’t know what to think! Hopefully it will be that interesting, but usually it’s not, so you’ll have to do some radio tricks to keep people engaged. But if you have a really hot piece of tape, something really genuinely interesting, if you start with that, people will give you a lot of leeway as they go with you. People will forgive me for a bad 4-minute story. They probably won’t forgive me for a bad 15-minute story. That’s a long time, or a bad half hour. It better be really, really good if I’m going to take up a segment on All Things Considered.

5. Your voice, your tone and style of reporting, is literally part of the story. How do you balance being relate-able and professional? Is it hard to control bias when your voice is clearly heard?

When it comes to business reporting … I think that the people around me are really clear about being fair. I think ‘Am I being fair to this person? Am I being fair to this idea?’ That to me is the paramount thing. Am I, if I do a story about this, am I thinking about the six sides that go into this?

I cover the auto industry. I don’t have a lot in stake emotionally in any of them. I am a child of an auto worker. My mother worked for Ford, my grandfather worked for General Motors, so I have an affinity for the industry. It’s just really nuanced. The only place I feel like I have a bias is I hate some cars. Just being like ‘that’s the worst car,’ and Robert Segal isn’t going to ask me on All Things Considered what I think of the latest blank, but I definitely have, some aesthetic opinions … and this car company is boring and this car company is stylish and sometimes even those opinions slip out, but I don’t think those opinions care the weight I think a political opinion would.

I’ve learned it’s important to be yourself and for you to be real on the radio. That makes it easier to voice, it makes it easier to talk, to interview people and all those things. I think being yourself means being professional, not pretending like you’re some blank slate. I’m a 6-foot-1, 200-lb. black man. I move about the world in that way. I can’t pretend, that’s not a thing. Oh and I’m gay and blah, blah, blah! It would be silly for me to try and control those things. I think at least people will realize that, and they’ll get that.

I think it works for me whether I’m covering cars or politics or art or whatever. Being a professional means bringing to the table who you are and being fair to the people you’re covering because you do definitely have an impact on the stories and the people you’re talking to. You can pretend, or you can be for real.