You might find this hard to believe, but a century or so ago, walking was a spectator sport. Thousands of people lined the route taken by Edward Payson Weston in 1909, when he spent four months walking from New York City to San Francisco.

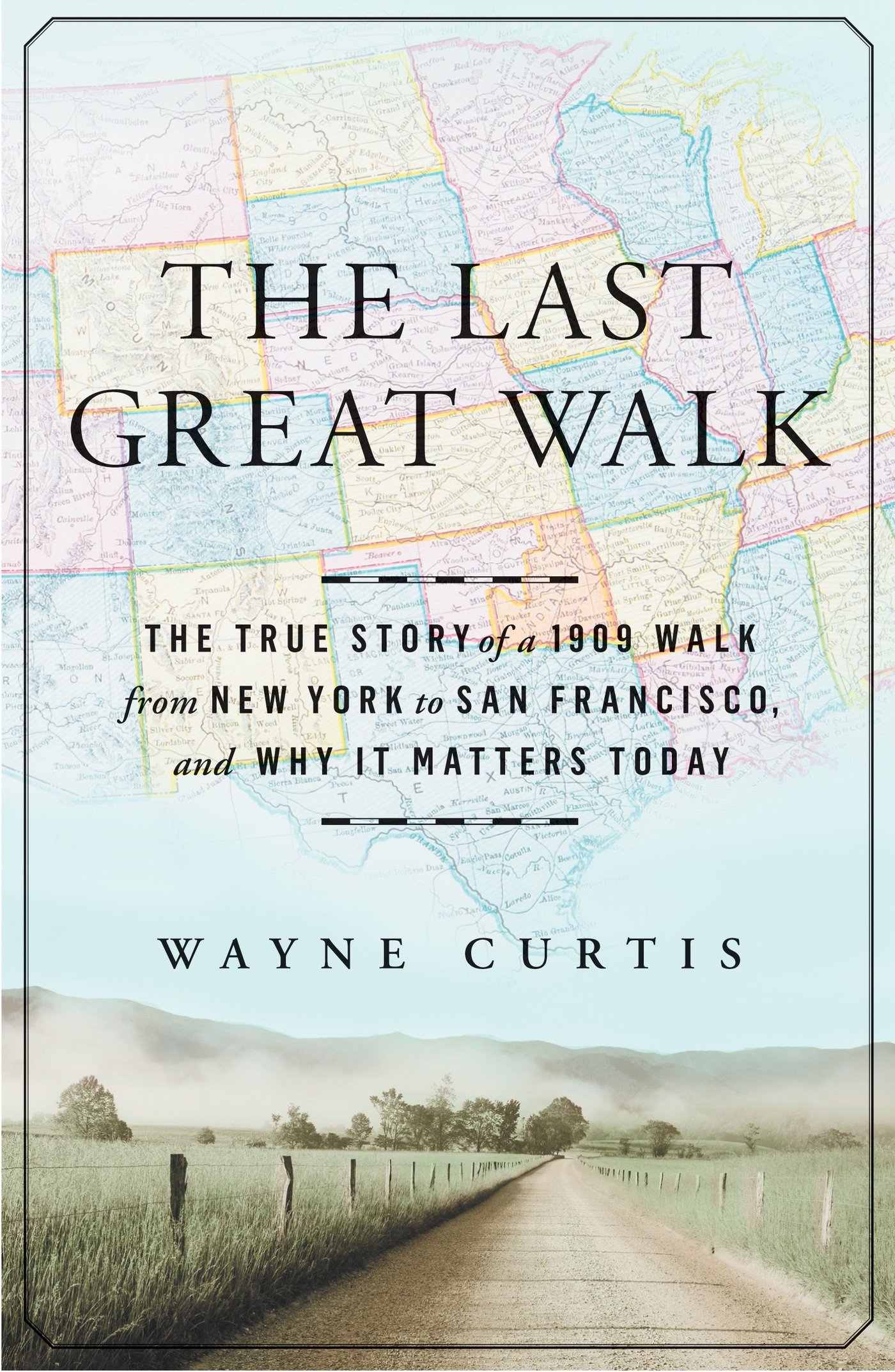

In his new book, The Last Great Walk, New Orleans-based writer Wayne Curtis tells how Weston, then age 70, turned his walk into one of the master marketing campaigns of the early 20th century. He walked 40 miles a day, attracting media attention that any celebrity would envy now.

We asked Curtis about Weston’s walk and why it became a sensation.

Give us a sense for the kind of celebrity that Weston was in his prime. Who would you compare him with?

Weston was basically the Michael Jordan of walking — he was both a talented athlete and a celebrity. Like Jordan, he was certainly a master in his world, and many today consider him the greatest walker of all time. But he was also charming and fun to interview, and he understood the press and found ways to make it work for him. Also, he had a hard time figuring out when to hang up his spurs.

What were some of his most successful marketing efforts?

Weston’s marketing was mostly old-school. He gave a lot of lectures in the evenings, often at the end of a long day of walking. People would flock to auditoriums, churches, and the like to hear him talk about his life as a walker and the benefits of walking. These sorts of talks were common and popular forms of entertainment in the latter half othe 19th century, and it allowed him to get the word out about walking and himself.

It didn’t hurt that telegraphs were becoming commonly used when he was active, and phone use was starting to grow during his 1909 cross-country walk, so people could notify friends and family down the road that he was headed their way, and that would bring out more crowds at the next stop. He also had a manager for his walks, and they presumably helped with marketing and getting the word out, but I didn’t find any real documentary evidence of how they went about this.

By the time Weston was conducting his epic walks, there were automobiles, trains and the airplane was becoming more than a curiosity. It seems counter intuitive that someone could draw attention on two feet. How do you explain the fascination?

This paradox is in large part what drew me to the story. The walk itself was interesting, of course, but I was more intrigued that the accounts I read reported that hundreds or thousands of people came out to watch him walk past.

I had to wonder, well, what’s going on here? I think the attraction was largely celebrity… he had been famous in the post-Civil War years for his prodigious feats of pedestrianism, and people who remembered him wanted to see him, as did their offspring who may have grown up hearing stories about him.

But more so, I grew to believe that there was a John Henry element in this story, man vs. machine, and Americans wanted to see him walk by as we entered into the automobile age, and long-distance walking as a matter of course was on the cusp of eclipse. At least that’s the case I make in the book, and why I titled it “The Last Great Walk.”

His first walk, to San Francisco, took him four months. That’s a long time to stay in the public eye. Tell us how the country reacted to him.

The interest in his walk seemed fairly widespread. He contributed updates two or three times a week to the New York Times, although the paper didn’t have the national reach it has today. And local reporters would file stories along the way, and these would get picked up though wire serves by cities far from his route, so it was clear that interest wasn’t just regional. There were some cynics out there — on his finish, a Chicago reporter noted that his arrival in San Francisco proved what “we have always maintained, that two times two are four.” But most accounts were far more laudatory.

When he subsequently walked to New York City, he drew big crowds, but then his celebrity began to fade. Did Americans just get tired of the walking craze? Did he contribute to the lessening of interest?

I think the novelty of his long walks had worn off, and he knew this. “The public doesn’t care anything about me, except as a sort of curiosity, a young old man,” he said after arriving in NYC in 1910. Public attention was no less fickle then than it is now. Motor cars and speed were gaining attention, and people moved on, literally. After five million years of walking about fairly slowly, being able to move at 10 or 20 times the speed of foot was far more interesting to most people.

So, imagine that Weston decided to set out on one of his long walks now. How do you think he’d publicize it? Could someone capture this kind of attention in a constantly updating world?

People are walking cross country all the time now on personal missions, mostly invisibly. Some seek publicity to raise funds for a cause, and it’s a struggle for many to rise through the information clutter. But many are just doing it simply because they’re drawn to the idea of making it from ocean to ocean on foot.

If Weston were setting off today, he’d certainly want people to notice. I’m pretty certain he’d have a blog, a Facebook page for himself and his walk, and he’d no doubt be tweeting constantly. So much so that I suspect he’d be somewhat insufferable, and I’d have to unfollow him.

You’re upfront about the fact that you didn’t re-trace his steps, but you did a lot of walking. What did you learn about walking, and in doing so, did you gain an appreciation for his feats?

I certainly gained respect for the 40-mile day (never mind the 70-mile day, which he could do and is still unfathomable to me). I tried several times under controlled circumstance to do 40 miles in a day, and I pretty much failed miserably each time.

I learned that my upper limit in urban walking is about 24 miles, and after that I’m just fatigued. But I also learned that 8 to 12 miles is a sweet spot, and that makes for a good afternoon’s exploration. I’ve also drunk the 10,000-step Kool-Aid, wearing a FitBit and trying to hit that mark every day (it’s about five miles).

I’ve found that if I can do that, the 8-12 mile walk will come easily. If I slack off for a while, then a longer walk leave me creaky and hobbled at the end. I guess it’s a bit like yoga — if you do it two or three times a week, you still feel pretty limber the next week. If you miss a week or two, you feel like you have to start over.

We still see stunts going on by daredevils, like Nic Wallenda. This is sort of an anti-stunt, given than anyone can go out and walk. However, do you see any parallels in the interest in Weston then and people like Wallenda now?

I suspect Weston had a great appreciation for stunts and the attention they could garner, even though his skill was one that anyone could do, and least in smaller doses. Weston certainly liked to attract attention. He dressed up like a dandy — big hats, walking stick, kid gloves — when walking through cities (although he’d strip down to simpler duds when pegging through the countryside).

And he was always racing against a clock, which gave his walks a tension and uncertainty, effectively making each walk a stunt, although not one with deathly consequences, as with tightrope walkers or motorcycle jumpers. But spectators always like to see people push limits and challenge themselves, and Weston offered a small spectacle in that regard.

Sign up for our newsletter and enter to win The Last Great Walk

Sign up for our newsletter and enter to win The Last Great Walk