Investment Accounting

Most entities maintain an investment portfolio that includes bonds, shares of stock and derivative securities. Entities maintain investments for a myriad of reasons including investing extra cash until it is needed for expansion or used to pay dividends, bonuses or buy-back shares. But issues exist with investments to the point where the FASB recently finalized a new accounting standard update, effective 2018. Because investment accounting is more complicated than it probably ought to be, let’s explore the accounting for debt investments in this article and the accounting for equities in next week’s article. I’ll highlight several of the issues capital market participants acknowledge surrounding debt investment accounting that may help you generate article ideas.

Accounting for Debt Securities

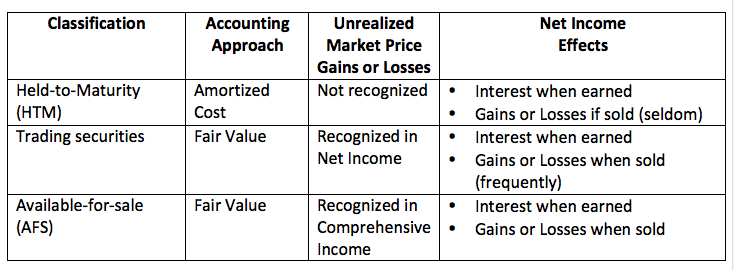

When managers purchase debt, they record the debt as an asset at the price paid. They then classify the debt security into one of three categories as shown in the table. These three categories are important because the accounting differs among them.

HTM Classification

The different classifications and accounting exist because the FASB acknowledges that entities purchase debt for different reasons. When managers purchase a debt security as an investment they could intend to hold it until it matures, thus receiving the maturity value of the bond; they could choose to actively trade it, hoping to generate trading gains; or hold it as an investment that isn’t actively traded but isn’t expected to be held-to-maturity either. Depending upon their intent, managers classify debt securities into one of these three classification categories. The accounting then follows the classification. In practice, managers classify almost all debt investments into the HTM or AFS categories. Almost never do they use the trading classification for reasons discussed below.

Managers purchase debt for varying reasons intending to hold it until it matures. Perhaps they are purchasing local government debt to help support schools, roads and other infrastructure. Perhaps managers of a large entity are purchasing debt of smaller suppliers to help the smaller supplier acquire funds to build new manufacturing plants to expand capacity (which the large entity wants to meet its own production needs). Holding to maturity is one of many financially sound investment strategies. There are many other reasons to hold bonds until they mature.

The HTM accounting reflects the intent to hold to maturity. At maturity, managers receive the maturity amount of the debt and they know that amount when they purchase the bond. Given the HTM intent, the FASB determined that there is no reason to record changes in market value of the debt security while it is held because market value changes will offset each other over time and eventually, managers will receive the known maturity value of the bond. Referring to the table, unrealized market value gains or losses are thus ignored for HTM bonds. Managers tend to like this accounting because the effect on net income is highly predictable.

Technically HTM accounting is “amortized cost.” Here’s the idea: If an entity purchases a bond today for $9,800 and the bonds’ maturity value is $10,000, the $200 difference is viewed as extra interest in addition to the coupon rate of interest. This $200 is amortized (i.e. recorded) to increase interest income from the date of purchase to the maturity date. If the bond had been purchased for $10,300 then the $300 difference would be viewed as a subtraction from coupon interest and the $300 amortized to decrease interest income from the date of purchase to the maturity date.

Trading Classification

Suppose an entity purchases a bond and intends to earn short-term trading gains. The FASB then reasoned that market price changes for the bond are important to measure financial performance. Reflecting management’s intent, the FASB requires bonds categorized as trading securities to be recorded on the balance sheet at fair value (not amortized cost like HTM bonds). Short-term bond price gains or losses are recorded as part of net income, again reflecting managers’ intent.

AFS Classification

Many entities purchase bonds that they don’t intend to hold to maturity but aren’t actively trading either. Managers classify these bonds as AFS securities. Again, the accounting reflects management’s intent. Since management isn’t holding the bond to maturity, market price changes are recorded in income. But since management isn’t actively trading the bond, market price changes are recorded only in comprehensive income, not net income. If the bond is eventually sold, then gains and losses recorded in comprehensive income are reclassified to net income.

Accounting Games with Bond Investment Accounting

Very few managers classify bonds as trading securities. Why? Managers know that they will be judged based on net income. It is no surprise then that managers want to control (manage) net income. If you consider the accounting for trading securities, changes in bond prices are recorded as part of net income. What if a negative market-wide event occurs on the last day of the year? Bond prices would go down and the loss would be recorded in net income. That means that an event outside of management’s control could cost managers their bonuses, cause earnings not to meet managers’ forecasts, and could overwhelm otherwise positive operating profits. Managers realize this possibility and have almost unanimously decided not to trade bonds (or equities). As anecdotal evidence, I recall that when these accounting principles were first implemented (well before year 2000) manufacturing entities all had trading portfolios. But a year after the new accounting was required, almost all U.S. public entities had rid themselves of trading securities, presumably to avoid possible volatility in net income from the accounting.

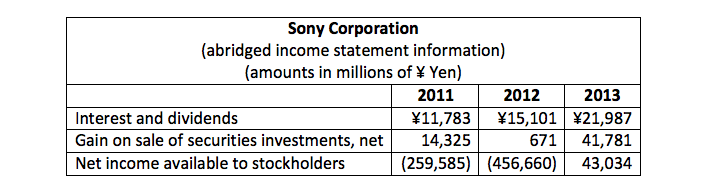

A more sinister game is to build up a large AFS portfolio of bonds (and equities) then time the sale to manage net income. Suppose an entity’s earnings on the last day of its fiscal year were just below expectations. Selling AFS securities that have market gains reclassifies the gains from comprehensive income to net income, allowing managers to claim that they met expectations. Does this behavior occur? Many managers and capital market participants believe so, although I have not seen a detailed, systematic, academic research study of this behavior. There is academic evidence that points to this behavior. Here are disclosures from Sony Corporation. What do you think?

Sony’s gain on sale of securities is trivial for 2011 and 2012, when Sony recorded large losses. Sony managers were under pressure to improve operations and show a profit. At first glance, they did so in 2013. But apparently almost all the profit came from managing investments. Footnote details disclose that they sold investments to generate the ¥41.781 billion gain (and positive net income). Was it coincidence that the gains from security sales generated a substantial percent of Sony’s net income? Well, that’s a potential investigative journal article. Many similar examples exist.

Investments may not be readily available to pay dividends or invest in operations. If we explore Apple, Inc.’s June 25, 2016 quarterly balance sheet, we see short-term marketable securities of $43.519 billion and long-term marketable securities of $169.764 billion totaling $213.283 billion. Total recorded assets are only $305.602 billion so, surprisingly, the marketable securities are the largest assets on Apple’s balance sheet. If Apple used the funds to pay a dividend they would first have to repatriate the investments to the U.S. and pay a repatriation tax. That tax could be as high as 33 percent, representing the U.S. tax rate of 35 percent less the approximately two (2) percent rate Apple has incurred on its non-U.S. earnings. Two percent is not a typo. Years ago Apple negotiated this low rate with the Irish government. Details were contained in Apple’s congressional testimony made in 2013 that is publicly available. It appears that Apple will continue building up its investments due to tax law motives. It would be interesting to observe Apple’s behavior if the U.S. government offered a “tax repatriation holiday” that various U.S. Congresspersons have discussed.