The day a company first sells stock shares to the public marks a right of passage. The initial public offering or IPO means the company is able to meet the long list of legal requirements that govern the trading of stock on a public exchange. It also means the company has been able to convince enough investors to buy the shares at a price that meets corporate fund-raising goals.

Fundamentals of common shares

A share of stock represents an equity stake, an ownership interest in the company. Exactly what rights the shareholder acquires depends on the kind of stock issued. We are usually talking about common shares, which convey at a minimum a right to a proportional share of the assets of the firm, after deducting liabilities, and a right to a share of any profits. Common shares usually confer a right to participate in the governance of the firm by, among other things, voting for members of the board of directors. But how much of a voice the shareholder actually has can vary greatly from company to company. This is one of the many factors an investor should consider before buying shares, and something your reporting should include.

Reporting on IPOs

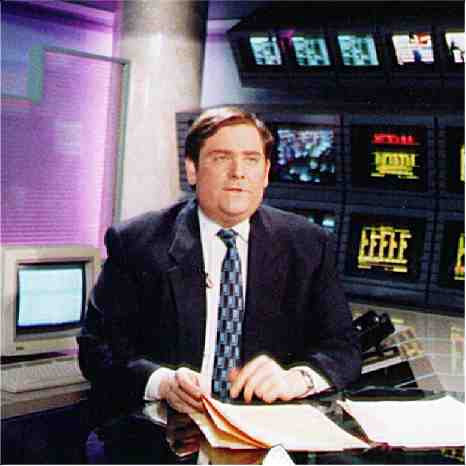

I’ve reported on some highly anticipated and record-setting initial public offerings. Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, just to drop a few names. These were all companies that had brands, products, high visibility—and in some cases, even profits—years before they first issued shares to the public. But most companies make their initial public offerings in relative obscurity, growing in stature as their business grows in the years following the IPO.

In reporting on an IPO you want to start with the regulatory filings the company has made in the run-up to the first trading day. Start with the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Edgar database. First and foremost is the “Form S-1 Registration Statement under the Securities Act of 1933.” The document is often revised several times until IPO day. Early versions carry “preliminary” labels in red ink and earned the nickname “Red Herring.” The statement is dense, formulaic and obscure, but buried inside are the little warts and blemishes of the business, as well as its assets and prospects, all valuable material when you are introducing the company to your readers.

Digging into the Edgar database

Once you are in the statement, look to see if the company is making any money, or if not, if it has a definite timetable for achieving profitability. Look to see who the early investors were, and how much control they were given in return for their investments. See how much of the ownership is being sold to the public, and how much is still retained by the founders. Look to see if there are outstanding legal, regulatory and/or competitive issues disclosed. Pay close attention to footnotes. All kinds of interesting information is often buried in these.

The IPO is probably not the first time stock shares have been distributed by a company. Shares frequently go to early-stage investors. After developing a product or service for which there is demand, funding growth is usually a company’s second biggest challenge. Early funding may come from the founder’s savings and from family and friends. A small business was once able to find a friendly face at his neighborhood bank, but small business loans are difficult to obtain in these days of bank consolidation. That leaves what the regulations call “sophisticated investors.” These are the venture capital firms, hedge funds and well-heeled individuals who are expected to do their own due diligence and can afford to take big risks. Some of the proceeds of the IPO are often used to pay this group of investors. You want to see how much will be used for that purpose.

How to use other sources

The great thing about the internet is that it allows almost anybody to publish anything, greatly facilitating the research process. This is especially true of material filed with or generated by a government in the normal course of its operations. The problem with the internet is that almost everybody does publish everything, and you need to always consider the source. So Google a company to your heart’s content. There is also nothing wrong with looking at Wikipedia and the specialized Investopedia. But know the difference between primary sources, which you can use for attribution, and the many opinions you will find. “Reports” that tout shares of a company should be regarded with skepticism.

After the IPO

The company collects the proceeds of the IPO after expenses, which include regulatory fees and often a hefty cut to an investment banker. These new funds can now be used to build the company. Buyers of those IPO shares are free to trade them away on the exchange, and these secondary market trades will continue for the life of the shares. But unless it buys and sells its own shares, or issues additional new shares, the company does not participate in the profits or losses from the secondary trades. While the company and its advisors took great pains to select the right number and price of shares to offer during the IPO process, from this day forward the market will set the price. Future gains and losses belong to the shareholders, not the company.

My next post will go into the dramatic 21st century changes that have turned the once-staid universe of stock exchanges into a plethora of trading platforms. Turn-of-the-century traders—and by that I mean the last turn—would barely recognize it.

Reporter’s Takeaway

• Journalists should look at the key points investors consider before buying a common stock, including how much of a voice a shareholder will have in the company

• The first place to look when investigating an IPO is the government’s Edgar database, which contains valuable details and background on the company

• Look into how much of the proceeds of an IPO will go to the initial group of investors

• The internet, including sources like Investopedia, is great for initial research, but regard secondary sources with skepticism