I have a routine that I have followed most Sunday nights for so long you could call it a ritual. At 11:55 p.m. I tune into my local news radio station for about 10 minutes, listening to a business report and the hourly network news. The idea is to learn if the world, to which I have been paying little attention over the weekend, is still intact. Also to get a general idea of what the big market stories will be on Monday morning, and particularly how trading is going on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, where Monday is well under way.

Invariably the announcer will read a story that begins, “Stocks begin trading tomorrow at blah-blah-blah…” The blah-blah-blah being a long number in the tens of thousands with a few decimals to boot.

Earlier in my career this bit of news copy would provoke a holler of pain. These days I just shrug my shoulders and turn out the light. The change is either a reflection of my maturity or my resignation. Perhaps both.

So what is wrong with the business report?

A couple of things. First, it seems a little silly to say that stocks begin trading tomorrow when the same announcer has just reported that stocks are trading right now in Tokyo. Apparently he or she meant to say that stocks will be trading somewhere else tomorrow, but hasn’t specified where. The announcer also said that stocks will begin trading at a number, but hasn’t explained what the number means.

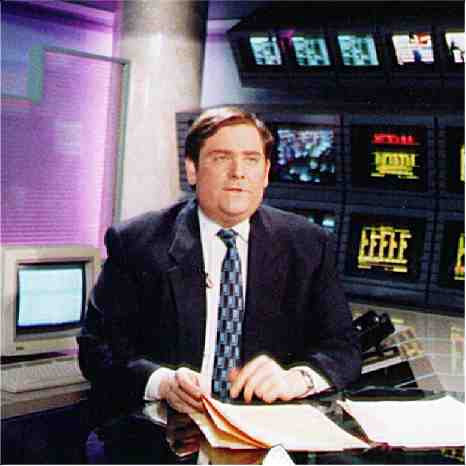

The man behind the rant

Think I’m being too picky? A lot of people would. I’ll tell you why I disagree in a moment. But first, by way of introduction, let me explain who I am. For longer than I want to reveal I was the New York Bureau Chief and Senior Correspondent for the public television program, “Nightly Business Report.” I reported on everything that moved in the New York area for the half-hour broadcast, which was seen weeknights on U.S. public television stations and at various times in many other parts of the world.

I have a Bachelor’s degree in Politics from Princeton University, a Master’s in Journalism from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Business Administration from the University of Chicago. I have taught journalism at Loyola University of Chicago and have lectured, participated in panel discussions and advised students at Princeton, Columbia and New York University. I have also participated in programs organized by the Reynolds Center, which led to the invitation to contribute to this blog. Hopefully what I will impart will be of value to journalists just starting their careers or just beginning to cover the financial markets.

I come from a school where reporting the news was seen as something different than commenting on the news. I helped write a standards manual for CBS which stated in no uncertain terms that reporters kept their opinions to themselves. How times have changed. I tell you this because I will try, as this series unfolds, to refrain from using rants such as the one which is driving this first piece.

Still, in my humble opinion, it pays to keep in mind a few guidelines which have served me well over the years. In the era first of broadcast news and now of online delivery channels for information, a lot of detail gets lost. But that is not an excuse for a lack of precision. You can’t say a lot in a minute and a half or in 140 characters. But you can take care that what you say is accurate and unambiguous.

Back to the radio

Which brings us back to where stocks will begin trading tomorrow. An educated guess would be that the writer is talking about the New York Stock Exchange, and that the long number was the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the world’s best-known stock market measure, calculated when the regular trading session ended at 4 p.m. Eastern Time the previous Friday. But why make a listener guess at the meaning? Why not say what you mean with enough precision to remove the ambiguity?

So we’ll state that the listener has made the right assumptions and ignored the fact that we are reporting that stocks will begin trading tomorrow when we’ve just reported that stocks are trading right now in Tokyo. The copy is still wrong.

We’ll go into greater detail in a future post, but for now it is enough to know that the Dow average is computed by adding up the price at which the last trade was made for each of the 30 stocks in the average, and then dividing by a number known, conveniently, as the divisor. In order for the Dow to begin Monday at the same place it ended the previous Friday, either every one of the 30 stocks has to begin trading at its Friday closing price, or the differences across all 30 stocks have to cancel out, generating the same sum. Possible? Yes. Likely. No.

And the moral of the saga is that numbers have meaning. In reporting on financial markets, the numbers mean money and jobs, success and failure. Precision is an essential fundamental.