Explosion of indexes

In a previous post about indexes, I identified the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Standard and Poor’s 500 as the two most frequently referenced. They originated as short-cuts that summarized market trends, and are often used as a benchmark against which investment performance can be judged.

There has been an explosion in the number of indexes in recent years. There are hundreds if not thousands available, enough to slice and dice the markets in as many ways as can be imaged. Some are broad-based, like the NASDAQ Composite with more than 3,000 stocks. Others might track a region, like the EURO STOXX 50, based on 50 large companies in the Eurozone. Some follow companies of a certain size, like the Wilshire US Small Cap. And still others focus on an industry, such as the NYSE Arca (originally AMEX) Semiconductor Index.

These finely tuned indexes help in the performance evaluation process. It is better, for example, to compare the performance of a semiconductor manufacturer with the Semiconductor Index than with the market as a whole. But it should be no surprise that the rapid growth in the number of indexes has corresponded with the rapid growth of investment products based on them. These provide increased options for investors, and of course increased profit opportunities for the financial services sector.

Mutual funds and active investing

The products include mutual funds, which some historians trace back to 18th century Netherlands. Here’s how it works. The more diversified an investment portfolio, the lower its risk. If an investor buys stock in just one company, her fortunes rise and fall with that one company. Buy two companies, bad news for one might not affect the other, especially if it is not making the same kind of product or is in other ways distinct from the first. The goal of diversification is to spread out your funds as broadly as possible.

But a single investor has limited resources. And the transaction costs, such as brokerage commissions, cut into portfolio returns. In a mutual fund, the investor puts money into the fund. The fund managers pool the assets and buy a selection of stocks. The investor now owns a share of an asset that is much more diversified than she could afford to buy on her own.

The investor also benefits from professional advice. A professional fund manager should be better at picking stocks than most individuals. This is called active investing. The Massachusetts Investors Trust, created in 1924, is believed to be the first modern day mutual fund with professional management.

Professional management might help spread out transaction costs, but these fund managers are not in business for their health. Funds have management fees, often charging an annual percentage of the assets under management. There may also be “loads,” sales fees charged when buying and/or selling the funds. With the increase in the number of indexes, investors could compare the performance of their funds with the index benchmarks. Studies showed that many funds were not performing any better than the benchmark and often, when the fees were considered, were doing worse.

The birth of member-owned mutual funds

In 1975, John Bogle (always one of my favorite interviewees when I was at PBS), responded to these revelations by founding Vanguard, a mutual fund company owned by its members. That meant it was not designed to earn management fees and could instead pass on its economies directly to investors in the form of lower costs.

Vanguard’s creation corresponded to a major change in the way American companies handled employee pension funds. These funds had traditionally been defined benefit programs, in which the company put aside money for the employee and either managed the fund itself or hired a professional to do it. The company was responsible for ensuring the employee would receive a regular fixed payment in retirement.

The new model moved the risk to the employee. In these defined contribution programs, the employer makes payments into a fund which the employee manages. It is up to the employee to make sure the money is invested well and will be there at retirement.

Index funds and passive investing

Vanguard’s low-cost funds, which understandably disrupted the mutual fund industry, became very popular with pension investors. And Vanguard innovated again with what is now called passive management by creating the Vanguard 500, a fund designed to mimic the S&P 500 index. The whole idea of index funds is not to try to “beat” the indexes, just to perform as well. This completely eliminates the need for expensive stock pickers employed by mutual funds. Computers simply keep the portfolio in balance with the index. This provides better performance with lower risk, just what employees faced with making their own investment decisions—in many cases for the first time—were looking for.

Reporter’s Takeaway

• There has been tremendous growth in the number of indexes available. They allow investors to evaluate companies that are similar in size, that are part of the same industry or that operate in a specific region.

• Indexes can be used to evaluate the performance of actively managed mutual funds, which charge management fees in return for actively picking stocks.

• Indexes also facilitate passive funds, which mirror the performance of the index. These lower risk index funds, managed by computers, also charge lower fees.

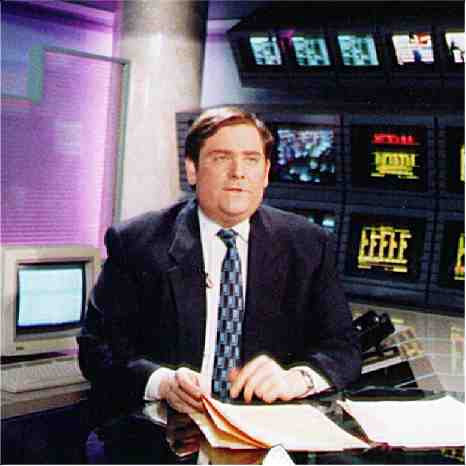

In his longtime role as New York Bureau Chief and Senior Correspondent for public television’s Nightly Business Report, Scott Gurvey covered the financial markets, business and the economy for the first and longest-running daily program dedicated to financial news on broadcast television. Currently Gurvey writes for various online sites, teaches the next generation of journalists and advises companies and nonprofits on media relations, communications strategy, ethics, newsroom operations and online application design and practice. His blog, “Public Offering,” lives at http://blog.scottgurvey.com, and Gurvey has been known to Tweet at @scottgurvey, from time to time.