In much of the United States, owning a car is a requirement to fully participate in society – for work, school and daily life. For millions of people shut out of traditional credit systems, subprime auto lenders have positioned themselves as the gatekeepers to mobility.

Over the past decade, those lenders grew quickly, fueled by investor appetite for high-yield debt and by a narrative of financial inclusion aimed at immigrant and low-income communities.

That all came to a halt on Sept. 10, 2025, when Tricolor Holdings, one of the industry’s fastest‑growing companies, filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. “The goal is to wind down the company, sell its assets and ensure that the company is no more at the end of the process,” said Laura Coordes, a bankruptcy law professor at Arizona State University.

Federal prosecutors allege that representations Tricolor made about its financing and collateral masked a scheme that misled lenders and investors for years. The indictment states that Tricolor founder and Chief Executive Officer Daniel Chu and Chief Operating Officer David Goodgame systematically misrepresented the quality and value of the company’s auto-loan collateral, allowing the firm to grow and raise capital even as its loan portfolio weakened. When the company collapsed, lenders and investors were left exposed to potential losses of more than $900 million.

The start of Tricolor

Tricolor painted a much prettier picture of what it was doing. Founded in 2007 by Chu, the company set out to provide credit to immigrants, first‑generation workers, and families without Social Security numbers or credit histories.

For many of those individuals, subprime lenders like Tricolor represented their only path to car ownership. And that left them at the lenders’ mercy.

Eileen Díaz McConnell, a President’s Professor of sociology and transborder studies at Arizona State University, noted that limited access to traditional banks and credit often pushes people into exploitative arrangements such as money lending and subprime car loans.

She explained that Tricolor specifically targeted undocumented immigrants, who were often trapped by circumstance – needing a car just to survive. “It’s hard to get around, for example, in Phoenix, if you don’t have a car,” McConnell said. “And it’s hot during the summer, so it’s not like you could just walk or ride your bicycle.”

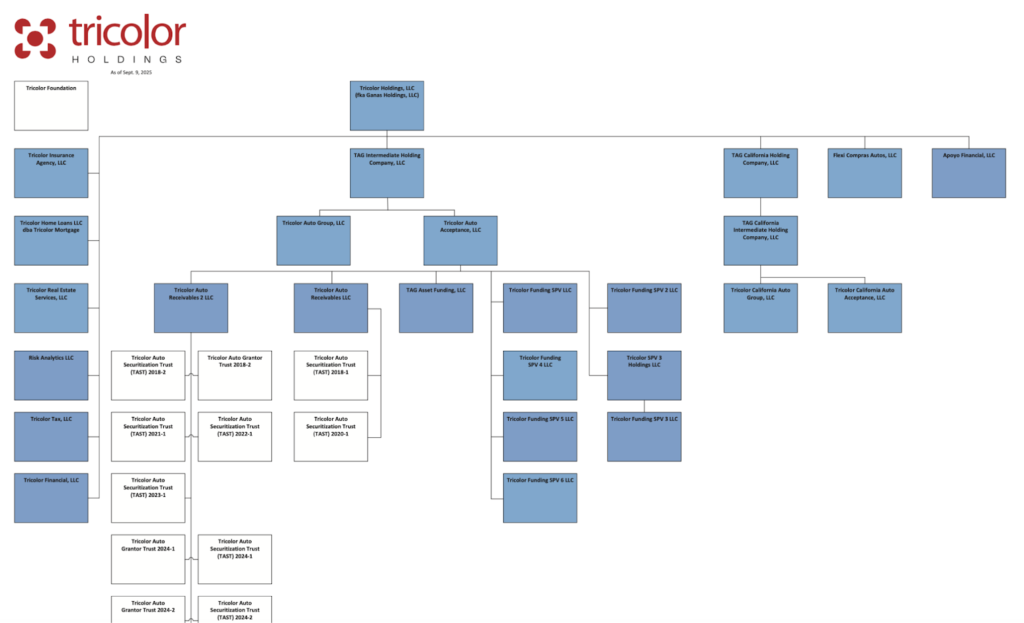

Tricolor’s lending business sat atop a tightly linked web of 18 entities controlled by Tricolor Holdings and its parent, Ganas Investors.

Within that structure, each subsidiary had a specific role: Tricolor Auto Group and Tricolor Real Estate Services handled sales and dealership operations, while Tricolor Auto Acceptance, Tricolor Financial and Apoyo Financial focused on financing and originating loans. Other units provided insurance and tax services, and entities such as Tricolor Auto Receivables and TAG Asset Funding were used to bundle customer loans into securities for investors.

By 2025, Tricolor had about 65 dealerships across Texas, California, Nevada and Arizona. According to court records, the company employed more than 1,500 people at its peak, generated roughly $1 billion in annual revenue in both 2023 and 2024, and had over 60,000 outstanding car loans at the time of its collapse.

Source: Bankruptcy court filing, corporate ownership chart

Tricolor’s model

To fund that lending machine, Tricolor used a common subprime-auto model: it borrowed short‑term money from banks and investment firms to fund its lending, then bundled and sold the loans it made. The company drew on several warehouse credit lines, including two listed in court records as Lender-1 and Lender-2, which advanced cash backed by used-car inventory and customer auto loans.

Starting in 2020, Tricolor set up several special-purpose entities known as SPV3 through SPV6 to hold car loans before selling them to investors. In simple terms, Tricolor would make a loan, place it into one of these entities and borrow money against it while waiting to sell it. To keep borrowing, the company had to show lenders that the loans were up to date on payments.

Under its financing agreements, Tricolor had to file frequent “borrowing base” reports, large spreadsheets with thousands of loans, whenever it needed more funding. The reports listed each loan’s delinquency status, from current to more than 60 days past due, along with details such as outstanding balance and recent payment dates. Lenders used that data to decide how much money Tricolor could draw from each credit line.

Over time, the reports became harder to follow. As prosecutors describe it, Tricolor kept its borrowing going by stretching the rules around what counted as collateral. That meant a single car loan, tied to one vehicle, was sometimes counted more than once, supporting borrowing from different credit lines at the same time.

In other cases, loans that were already behind on payments, or had been written off internally, were shown as current in the reports lenders relied on. That allowed Tricolor to keep borrowing against those loans, even though customers were no longer paying as expected.

In a July 2022 text message cited by prosecutors, Chu asked whether loans more than 60 days past due could be “worked” to keep them usable as collateral. Months later, Tricolor Chief Financial Officer Jerome Kollar reported that by shifting loans between delinquency categories, the company could increase how much it could borrow by more than $1 million. “Will do a BB tomorrow and work to squeeze a little more out,” Kollar wrote, referring to a borrowing-base report.

By late summer 2025, an internal review highlighted a mismatch between what Tricolor had reported to lenders and what its own records showed. The analysis, completed around Aug. 21, found a gap of roughly $800 million between the collateral used to support financing and the assets reflected in the company’s systems.

Lenders pressed Tricolor for answers in the summer of 2025. In recorded calls and messages cited by prosecutors, Chu discussed how to explain the discrepancies in the analysis, at one point suggesting a fictitious deferment policy he claimed dated to the first Trump administration. In other exchanges, executives called the discrepancies a “system issue,” even as internal records showed the data had been manually altered.

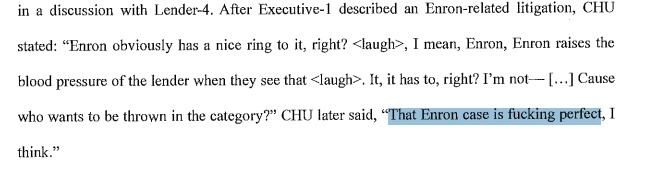

After learning that lenders had identified tens of millions of dollars in loans marked current despite months without payment, Chu used profanity to describe the situation, calling it “the stupidest fucking thing” he had heard, and pressed subordinates on why balances had not been reduced to match the altered payment histories. As one lender moved to terminate its facility, Chu discussed bringing up the fate of Enron, which collapsed in 2001 amid one of the biggest corporate scandals in history, in order to pressure banks to settle. He also suggested using artificial intelligence tools to identify language that could raise concerns for lenders about their own exposure.

Of Tricolor’s bank relationships, one stands out: Origin Bank. Chu served on its board, and the lender reported about $30.1 million in loan commitments to Tricolor, secured primarily by notes receivable. On Sept. 7, 2025, Chu told Origin Bancorp and its subsidiary, Origin Bank, that he was resigning from their boards effective immediately. The company said there were no disagreements.

Source: SDNY federal indictment (25‑CR‑579)

Tricolor was built on a moral narrative

Still, a central question remains: how did Tricolor keep these practices from its lenders for so long? Marianne Jennings, an emeritus professor of legal and ethical studies in business at Arizona State University, said Tricolor’s collapse fits a familiar pattern. Charismatic leadership, weak governance and a strong moral narrative can combine to reduce scrutiny, she said, even as risks build beneath the surface. “It’s so easy to build yourself up as one of the people, one of the good companies,” Jennings said. “It builds trust when there shouldn’t be trust.”

Much of that image came from Tricolor’s founder. In public appearances and interviews, Chu often framed his career as an effort to build institutions from the ground up. He studied at Cornell University for two years and later graduated from Washington University in St. Louis, a period he has described as formative. On a 2024 podcast with fintech investor Peter Renton, Chu said his parents’ experience as immigrants shaped his belief that Hispanic communities were underserved by traditional finance. The name Tricolor, drawn from the Mexican flag and soccer tradition, was chosen for its cultural resonance. Chu frequently described Tricolor as a data-driven company with a social mission.

“People equate social responsibility with ethics and they’re two completely different things,” Jennings said. “[Tricolor was] really saying, ‘Hey, we are serving a group of people who would otherwise not have this opportunity.’”

She noted that investors “pour money into this because it makes them look good in their glossy annual reports that talk about all they’ve done for the community.”

According to Jennings, that image of virtue created a powerful shield. When a company builds its brand as socially responsible, it “provides a cover.” The effect, she said, is that scrutiny fades. “You even have regulators who will not touch these companies because they are recognized as being so responsible.”

The strategy, Jennings added, is deliberate: to draw attention to good deeds so “nobody’s paying attention to what they’re really doing.”

Attempts to reach Chu for comment were unsuccessful. Tricolor also did not respond to requests for comment sent through the contact information listed on its website.

Where Tricolor is today

By the fall, the company itself had largely disappeared. When I visited Tricolor’s location at 1147 E. Camelback Road in Phoenix in October, the doors were locked and the lot was quiet. Faded flags hung in tatters. By early December, the vehicles were gone, though the sign still glowed. The company’s website carried a notice: “We are no longer offering financing or sales services. If you are an existing customer, please continue making your payments as usual.”

At a Nov. 18, 2025, creditors’ Zoom meeting, no Tricolor executives appeared.

As the company unraveled, court records show, Chu continued to draw substantial compensation. In the weeks before Tricolor’s collapse, he arranged a pay package including a payout of $6.25 million, which he used to buy a property in Beverly Hills, part of a broader package that included a $15 million bonus in 2025. Days later, Tricolor placed more than 1,000 employees on unpaid leave.